The diagnostic approach to hepatocellular carcinoma

Doris Schacherer, Jürgen Schölmerich, Ina Zuber-Jerger

+ Pracoviště

ABSTRACT

Schacherer D, Schölmerich J, Zuber-Jerger I, The diagnostic approach to hepatocellular carcinoma

Risk factors and symptoms of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The main risk factors of HCC include infection with hepatitis B or C virus, as well as alcohol consumption. There are no specific symptoms of HCC, making early diagnosis and detection of the disease difficult. When HCC presents with specific clinical symptoms, the tumor is typically very far advanced.

Surveillance in liver cirrhosis. The most common serologic marker used in HCC diagnosis is a-fetoprotein (AFP), but other tumor markers such as the des-y-carboxy prothrombin (DGCP) or fractions of AFP (AFP-L3) exist and there use is discussed in this context. Surveillance should be done by sonography at 6 (-12) months intervals.

The single nodule in the cirrhotic liver. Ultrasound is the most commonly used imaging modality in detecting HCC tumor nodules with a large range of reported sensitivities. HCC may appear as a hypoechoic, isoechoic, or hyperechoic round or oval lesion with intratumoral flow signals at Doppler or power Doppler sonography. The differentiation of smaller malignant lesions in cirrhotic livers can be improved by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Spiral computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast enhancement play an important role in the diagnosis and staging of HCC. If the vascular pattern on imaging is not typical, biopsy becomes necessary.

The patient with known HCC. Different tumor markers are used in the evaluation of tumor progression, prediction of patient outcome and treatment efficacy.

Among various staging systems used in the context of HCC, the Barcelona-Clinic-Liver-Cancer (BCLC) staging system is currently the only staging system, which takes into account tumor stage, liver function, physical status and cancer related symptoms.

Beside surgical resection, non-surgical treatments such as percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), radiofrequency thermoablation (RFTA) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) are used. Successful tumor "bridging" with ablative therapy methods can be achieved in carefully selected patients waiting for orthotopic liver transplantation. Contrast-enhanced sonography is able to control the ablation treatments of HCC.

ABSTRAKT

Schacherer D, Schölmerich J, Zuber-Jerger I, Diagnostika hepatocelularniho karcinomu

Rizikové faktory a smyptomatologie hepatocelulárního karcinomu (HCC). Hlavním rizikovým faktorem HCC jsou virová hepatitida B a C a alkohol. Žádné specifické příznaky HCC nejsou, a proto je jeho detekce obtížná. Pokud jsou klinické příznaky přítomny je nádor již značně pokročilý.

Sledování jaterní cirhózy. Nejběžnějším sérologickým markerem užívaným v diagnostice HCC je a-fetoprotein (AFP), ačkoliv se používají další tumorozní markery jako des-y-carboxy protrombin (DGCP) nebo frakce AFP (AFP-L3) a jsou v tomto textu diskutovány. Sledování by se mělo provádět sonografickými kontrolami v intervalu 6 měsíců, resp. 6-12 měsíců.

Jeden uzel v cirhotických játrech. Ultrazvuk je nejčastěji užívaným zobrazovacím postupem v detekci HCC tumorových uzlů se širokou škálou dokumentovaných senzitivit. HCC se může jevit jako hypoechogenní, izoechogenní nebo hyperechogenní oválné nebo kulaté ložisko provázené intratumorózním průtokovým signálem na dopplerovské nebo zesílené dopplerovské ultrasonografii. Rozlišení menších maligních lézí v cirhotických játrech může být zlepšeno kontrastním ultrazvukem (CEUS). Spirální CT a magnetická rezonance (MRI) s kontrastem nebo bez něho má důležitou úlohu v diagnóze a stagingu HCC. Pokud není cévní struktura typická, je indikována biopsie.

Pacient se známým HCC. Mezi různými systémy nádorových markerů užívaných pro HCC je v současné době pouze jediný systém stagingu, a to Barcelona-Clinic-Liver-Cancer (BCLC), který bere v úvahu velikost nádoru, jaterní funkci, fyzikální nález a symptomy nádorového onemocnění. Kromě chirurgické resekce jsou dále užívány nechirurgické techniky jako injekce alkoholu (PEI), radiofrekvenční ablace (RTFA) a transarteriální chemoembolizace (TÁCE). Úspěšné překlenutí tumoru pomocí ablativní léčby může dosáhnout u dobře zvolených nemocných vyčkání na transplantaci jater. Ultrazvukovým vyšetřením za pomoci kontrastu můžeme dobře sledovat efektivitu ablační léčby.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy among men and the eighth in women world-wide(1). Men develop HCC more often than women in all populations, with male-to-female ratios reported from 2:1 - 8:1(2).

In most high-risk countries, principal risk factors include infection with hepatitis B virus and dietary exposure to aflatoxin B. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the main reason for the high incidence of HCC in Asia. In contrast, hepatitis C virus and alcohol consumption are more important factors in low-risk countries. The European Association for Study of the Liver (EASL) single topic conference suggested that screening should be offered to patients with hepatitis C and stage 3 fibrosis(3). Hepatitis C virus coinfection dramatically promotes the development of HCC in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) wherefore these patients should undergo screening, too(4). Table 1 shows different groups of patients suitable for HCC screening.

Symptoms of HCC are similar to those of liver cirrhosis: fever, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, weight loss, fatigue and icterus together with epigastric pain and dullness. However, more than 40 % of HCC patients are asymptomatic from a tumor perspective, making early diagnosis and detection of the disease difficult)(5). When HCC presents with specific clinical symptoms, the tumor is typically very far advanced and the patient has almost no therapeutic options left. Thus, screening and surveillance for HCC appears to be very appropriate.

HCC is the most common form of liver cancer and might be unifocal, diffuse, or multifocal at presentation. The diagnosis of HCC includes detection of an index lesion and staging including number and diameter of hepatic lesions, presence of vascular invasion and assessment of extrahepatic manifestations.

SURVEILLANCE IN LIVER CIRRHOSIS

Surveillance in patients with liver cirrhosis is meaningful due to improved therapeutic options and acceptable tests in patients with high risk. However, screening for HCC involves more than simply applying one or more screening tests. Screening should be offered in the setting of a program or a process in which screening tests and procedures have been standardized. The purpose of screening involves deciding what level of risk of HCC is high enough to trigger screening, what screening tests to apply and how frequently, and how abnormal results should be dealt with. The primary aim is to recognize HCC at an early stage, when the tumor is potentially curable.

Tumor markers

The most common serologic marker used in HCC diagnosis is AFP, an α1-globulin produced in fetal cells as well as in regenerating and malignant hepatocytes. The AFP level is the most widely studied and used biologic marker for HCC detection and diagnosis, with a low sensitivity of 39 - 65 %, a specificity of 62 - 94 % and a positive predictive value of only 9-50 %(6-8). In 1994, Pateron D et al. prospectively studied 118 French patients with Child-Pugh A or B cirrhosis and without detectable HCC using an ultrasound evaluation of the liver and the determination of blood AFP and DGCP levels every six months. None of the screening methods did effectively identify potentially resectable tumors in this study(9).

In cirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis infection, high AFP levels may reflect both exacerbations of the infection and the presence of HCC. High titers of AFP (> 100 ng/mL) have been described in acute liver failure, pregnancy, massive metastatic liver involvement, and in the presence of germ-cell tumors(6). Due to its low accuracy, AFP levels should not be used as a screening test. The usefulness of other markers such as the DGCP or fractions of AFP (AFP-L3) has not been proven in this context and further research on this field is needed.

Ultrasound (US)

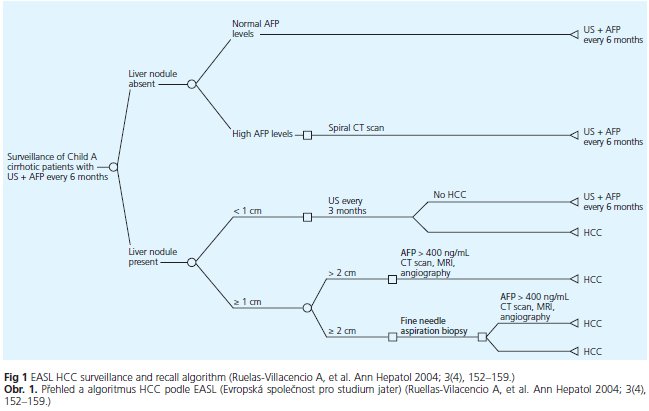

Sonography became available for identifying hepatic lesions in the early 1980s. The reported sensitivities of US imaging in detecting HCC tumor nodules range from 35 to 84%, depending on the expertise of the operator as well as on the US equipment< sup>(10). However, it is difficult to diagnose small focal nodular lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis due to diffuse parenchymal pathology in terms of diffuse inhomogenities of the liver parenchma and fatty liver changes. Liu WC et al. retrospectively reviewed pretransplantation sonography in 118 consecutive patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. This method depicted only 27 % of all hepatocellular carcinomas(11), which shows the difficulties of this method in cirrhotic patients. Combining use of AFP and ultrasound in increases detection rates, but also increases false positive rates(12). Due to Zhang et al, HCC screening with AFP and US every 6 months reduced HCC mortality by 37 %(13). Concerning the time intervals of surveillance of cirrhotic patients for hepatocellular carcinoma, both, the semiannual and the annual surveillance program doubled the prevalence of potential candidates for liver transplantation(14). Hence, there is no doubt about the importance of surveillance in patients with liver cirrhosis. Figure 1 shows the surveillance algorithm proposed by the EASL in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Summary - recommendations

- Patients at high risk for developing HCC should undergo surveillance.

- Patients with liver cirrhosis on the transplant waiting list should be screened for HCC.

- AFP still has a role in the diagnosis of HCC, since in cirrhotic patients with a mass in the liver an AFP greater than 200 ng/ml has a very high predictive value for HCC, but AFP should not be used alone unless sonography is not available.

- surveillance should be done by sonography at 6 (-12) months intervals(15).

THE SINGLE NODULE IN A CIRRHOTIC PATIENT

To characterize the nodules found within the cirrhotic liver parenchyma is imperative for the optimal management of these patients.

Ultrasound

US enables a rapid and noninvasive evaluation of liver parenchyma, although a comprehensive assessment may be impossible because of patient's body habitus. The ability to detect a small HCC is highly dependent on the expertise of the operator performing the examination. Of interest, no improvement in sensitivity was observed over the past decade despite the advances in US technology(16). At US, small HCC usually appears as a round or oval mass lesion with sharp and smooth boundaries that may exhibit a hypo-echoic, isoechoic, or hyperechoic appearance with respect o surrounding liver parenchyma. At Doppler or power Doppler sonography, HCC is usually presents as a vascular-rich lesion containing intratumoral flow signals. However, Doppler signals might be missed in smaller nodules so that this technique can not be considered ideal to confirm the hypervascular pattern detected in spiral CT. Color Doppler and power Doppler have increased the accuracy of US in the characterization of HCC's, because they allow the detection of the increased arterial flow(17).

HCC greater than 3 cm in size can be diagnosed with a high accuracy by conventional ultrasound. However, the differentiation of smaller malignant lesions in cirrhotic livers can be improved by CEUS(18) ). Arterial hypervascularity is considered a marker of HCC, and this is currently employed for diagnostic purposes when contrast-enhanced imaging techniques are used. Furthermore, evaluation of intranodular hemo dynamics is of value to characterize in-trahepatic nodules in the cirrhotic liver, because pathologic malignancy grades of HCC are closely related to intranodular flow patterns.

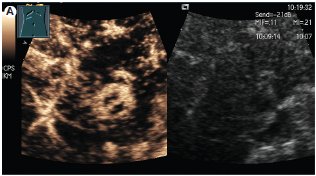

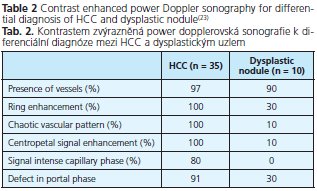

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of contrast-enhanced sonography is 89 - 96 %, 60 - 97 %, and 96 %, respectively(19-21), namely depending on nodule size(22). Hepatocellular carcinomas and regenerative nodules show a different contrast behaviour with echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography. A peritumoral signal detection in the early arterial phase, chaotic and centripetal intratumoral contrast enhancement in the arterial phase followed by rapid washout with an hypoechoic appearence in the portal venous and late phases are characteristics of malignancy(23). In contrast, regenerative nodules usually do not show any early contrast uptake and resemble the enhancement pattern of normal liver parenchyma. The criteria of contrast-enhanced power Doppler sonography in the differential diagnosis of HCC and dysplastic nodules is shown in table 2. Figure 2 shows the contrast enhancement in the early arterial phase and the typical wash-out phenomen in a patient with histologically proven HCC.

One limitation of contrast-enhanced sonography is its inability to characterize lesions distant to the applicator. In addition, this modality is more dependent on examiner skill. Today it is not clear whether CEUS can replace CT or MM in the characterization of suspicious liver lesions. At present, these techniques may have a complementary role.

Computed tomography

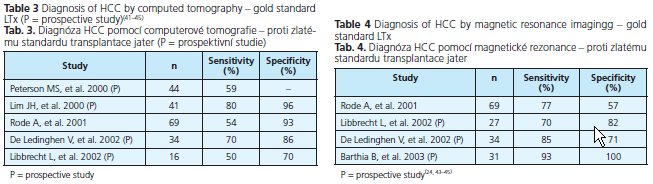

A triphasic hepatic acquisition helical CT scanning technique, which detects the presence of vascular nodules as positive indication of possible HCC, has become an additional standard method for clinical diagnosis. Despite these substantial technological advances, CT remains relatively insensitive for the detection of tiny HCC lesions. Only 10 to 43 % of lesions smaller than 1 cm were identified(16). Table 3 shows different studies evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of CT.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Over the past few years, MR imaging of the liver has progressed significantly with several liver-specific contrast agents being developed. In patients with a cirrhotic liver, double-contrast MR imaging is highly sensitive in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinomas of 10 mm or larger, but success in the identification of tumors smaller than 10 mm is still limited(04). Table 4 shows different studies evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of MRT.

Lutz AM et al. described marked variability of contrast enhancement pattern on Tl-weighted gradient-echo MR images with gadolinium or superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) contrast agents(05). In a study of Kim YK et al. super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-enhanced MF and multi-phasic CT shows similar diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and positive predictive value for the detection of HCC in patients with relatively mild hepatitis B-induced liver cirrhosis(26). However, Stoker J et al. demonstrated that SPIO enhanced MRI was superior to spiral CT for detection of lesions in patients at risk for HCC(27). SPIO enhanced MRI may be preferred as there is no exposure to ionising radiation.

In summary, both techniques (helical CT and MRI with contrast-enhancement) have an accuracy in the diagnosis of HCC exceeding 80-90 %(6) and have replaced angiography and CT hepatic angiography.

In a recent systemic review on the accuracy of AFP, US, spiral CT, and MRI in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma, the pooled sensitivity of 14 US studies was 60 % for sensitivity and 97 % for specificity. In 10 CT studies, the sensitivity for CT was 68 % and the specificity was 93 %, whereas for nine MRI studies, sensitivity was 81 % and specificity was 85 %. The sensitivity for AFP varied widely(28).

Biopsy

Well over half of very small nodules arising in cirrhotic livers may prove to be hepatocellular carcinoma and almost 90 % of these malignancies can be reliably identified with ultrasound guided-fine needle biopsy(29). If the initial biopsy is negative, repeat biopsy leads to diagnostic gain in one third of the patients, in particular if the first biopsy provided a non-diagnostic sample (necrosis) or a false negative result due to well differentiated HCC(30) ).

A problem associated with routinely biopsying suspicious lesions is the uncertainty associated with a negative biopsy finding. First, when the lesion is so small needle placement may be difficult and one can not be certain that the sample did indeed come from the lesion. Second, it may be difficult to distinguish well-differentiated HCC from normal liver on biopsy.

Although the rate of needle tract seeding after biopsy of small lesions has not been accurately measured, it is probably uncommon.

Finally, the risk of biopsy is small and the potential benefits are significant, especially for altering the treatment plan.

Diagnostic work-up

The prevalence of HCC among US-detected nodules is strongly dependent on the size of the lesion: whereas half of the nodules less than 1 cm in size are not malignant, the large majority of the lesions exceeding 2 cm are true HCC or contain HCC foci(3). The differential diagnosis between small HCC and a large regenerative nodule remains one of the greatest challenges in liver imaging.

Half the nodules < 1cm do not correspond to HCC and even if such a nodule corresponds to a true malignancy, it is almost impossible to correctly classify its nature with the current diagnostic tools. Thus, in these circumstances one should repeat US every 3 months until the lesion grows to more than 1 cm. When the 1 cm cut-off is exceeded additional diagnostic techniques are applied. When the nodule is 1-2 cm in size, the diagnostic confirmation should be pursued by performing two dynamic studies (CT, MRT or US with contrast). If diagnosis is not possible due to two imaging modalities, biopsy should be performed by an expert. However, a negative biopsy in a large hypervascularised nodule in a cirrhotic liver will never rule out malignancy. A nodule of more than 2 cm in size and with typical features in one dynamic study or with an AFP > 200 ng/ml is taken as HCC. A biopsy is not essential. However, if the imaging appearence are atypical, the differential diagnosis is broader, and tumor biopsy can get necessary.

Summary - recommendation (15)

- Nodules smaller than 1 cm should be followed with ultrasound every 3-6 months.

- Nodules between 1-2 cm found on ultrasound should be investigated further with two dynamic studies, either CT scan, contrast-enhanced ultrasound or MRI with contrast. If the appearance is typical for HCC in two techniques, the lesion should be treated as HCC. If not, the lesion should be biopsied.

- Nodules larger then 2 cm and with typical features of HCC need no biopsy. However, if the vascular pattern on imaging is not typical, biopsy should be performed.

- Biopsies of small lesions should be evaluated by expert pathologists.

THE PATIENT WITH KNOWN HCC

Tumor markers

The identification of sensitive and specific tumor markers for HCC have contributed not only to detection of HCC, but also to evaluation of progression of HCC and determination of patient prognosis. AFP levels can be useful as a confirmatory test for the presence of HCC once a liver mass is detected in a cirrhotic patient. However, there exists no statistical correlation between the AFP level, the total tumor volume and the growth rate of HCC(31).

There are three currently used tumor markers for HCC AFP, Lens culinaris agglutinin A-reactive fraction of AFP (AFP-L3), and DGCP, which is also called protein induced by vitamin K absence II (PIVKA-II). Toyoda et al. (32) conducted a prospective study to evaluate the significance of simultaneous measurement of these three markers in the evaluation of tumor progression and prognosis of patients with HCC. The number of tumor markers present reflected the extent of HCC and patient outcomes. Patients positive for AFP-L3 alone had a greater number of tumors, whereas patients positive for DGCP alone had larger tumors and a higher prevalence of portal vein invasion(32-33). In summary, tumor markers appear to represent different features of tumor progression in patients with HCC. The number of tumor markers present could be useful for the evaluation of tumor progression (tumor of higher stage if several markers are positive), prediction of patient outcome (worse prognosis in case of several positive markers), and treatment efficacy.

Staging systems for HCC

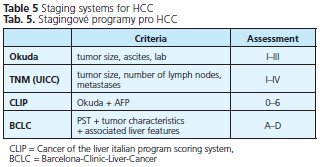

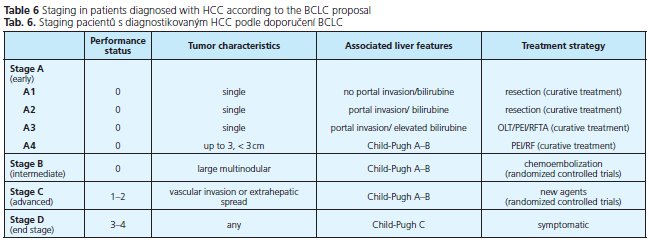

The prognosis of solid tumors is generally related to tumor stage at presentation and thus tumor stage guides treatment decisions. Well defined and generally accepted staging systems are available for almost all cancers. HCC is something of an exeption as many different staging systems have been introduced around the world and currently there is no consensus on which is the best. The prediction of prognosis is more complex because the underlying liver function also affects prognosis. In the past, HCC has been classified by the TNM or Okuda staging systems. The TNM system has been modified repeatedly and still does not have adequate prognostic accuracy. In addition, its use is limited because it is based on pathological findings and liver function is not considered. The most commonly used clinical staging system is that developed by Okuda et al. (34), evaluating the patient on the basis of clinical criteria such as the presence of ascites, serum albumin levels, bilirubin concentration, and tumor size. This system allows the identification of patients with end-stage disease, but is unable to adequately classify patients with early or intermediate stage disease. The Child-Pugh system only considers liver function and thus cannot be accurate. The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) system takes four parameters into account: Child-Pugh stage, tumor morphology, AFP level and vascular invasion and has been widely applied for outcome prediction in HCC patients. In summary, most classification systems do not take into account the effects of treatment, nor do they indicate optimal forms of treatment for different stages of disease. The BCLC staging system is currently the only staging system, which takes into account tumor stage, liver function, physical status and cancer related symptoms. The main advantage of this system is that it links staging with treatment options and with an estimation of prognosis that is based on published response rates to the various treatments. It identifies patients with early HCC who may benefit from curative treatment, those at intermediate or advanced disease stage who may benefit from palliative treatments, as well as those at end-stage disease with poor prognosis.

Table 5 shows different commonly used staging systems for HCC, table 6 shows the BCLC staging system in detail. We recommend to use spiral CT or MM for staging of HCC, depending on patients' renal function and age.

Treatment

Early detection of HCC is important as liver transplantation can cure patients with limited disease. One has to think critically about the necessity of taking a biopsy of every suspicious lesion in the cirrhotic liver of patients waiting for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). One reason for treating these patients with reserve is the small but existent amount of needle tract seeding. Furthermore, the number of patients in whom a liver biopsy of a nodule suspicious for HCC in a cirrhotic liver will change the decision for liver transplantation is fortunately very small. Liver transplantation may be considered the only fully curative treatment since it removes both the tumor and the cirrhotic liver. It results in better overall and disease-free survival than hepatic resection in patients with small HCC(35).

Beside surgical resection, non-surgical treatments such as PEI, RFTA and TACE have been used in HCC patients listed for OLT to prevent tumor progression. There is no standard treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, but arterial embolisation is widely used.

Contrast-enhanced sonography is able to control the ablation treatments of HCC, evaluating the former lesion with respect to complete necrosis or residual viable tumor. Nodules vascularized in the arterial phase on contrast harmonic ultrasound should be considered still viable and addressed by additional treatment(36-37). In patients with unexplained rising AFP after ablative treatment of HCC and if conventional examinations are normal, FDG-PET provides an important and valuable imaging study for detecting ex-trahepatic metastases, with a sensitivity of 73.3 %, a specificity of 100 % and an accuracy of 74.2 %(38).

Removal of HCC by surgical means offers the best chance for possible cure. Unfortunately, less than 20 % of patients meet the criteria for resection at the time of diagnosis(39). Successful tumor "bridging" with ablative therapy methods can be achieved in the majority of carefully selected patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding T2 criteria (single lesion, 2-5 cm; 2 or 3 lesions, all within 3 cm) and waiting for OLT(40).

Summary - recommendations

- OLT is an effective option for patients with HCC corresponding to the Milan criteria. Living donor OLT can be an option if the waiting time is long enough to allow tumor progression leading to exclusion from the waiting list.

- After any kind of treatment for HCC, surveillance should be performed in the same way as before therapy.

ABBREVIATIONS

AFP - alpha-fetoprotein; PIVKA - protein induced by vitamin K absence; DGCP - des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin; HCC - hepatocellular carcinoma; US - ultrasonography / ultrasound / sonography; CEUS - contrast-enhanced ultrasound; CT - computed tomography; MRI - magnetic resonance imaging; HCV - hepatitis C virus; HIV - human immunodeficiency virus; EASL - European Association for Study of the Liver; OLT - ortho-topic liver transplantation; TACE - transarterial chemoembolisation; PEI - percutaneous ethanol injection; RFTA - radiofrequency termoablation; SPIO - superparamagnetic iron oxide

References

- 1. Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 5-16.

- 2. Tangkijvanich P, Mahachai V, Suwangool P, Poovorawan Y. Gender difference in clinicopathologic features and survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10: 1547-1550.

- 3. Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, et al. EASL Panel of Experts on HCC. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona - 2000 EASL Conference. J Hepatol 2001;35:421-430.

- 4. Giordano TP, Kramer JR, Souchek J, et al. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected veterans with and without the hepatitis C virus: a cohort study, 1992-2001. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164: 2349-2354.

- 5. Gish RG. Hepatocellular carcinoma: overcoming challenges in disease management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 252-261.

- 6. Llovet JM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: patients with increasing alpha--fetoprotein but no mass on ultrasound. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 29-35.

- 7. Farinati F, Marino D, De Giorgio M, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of a-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma: both or neither? Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 524-532.

- 8. Daniele B, Bencivenga A, Megna AS, Tinessa V. Alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127: 108-112.

- 9. Pateron D, Ganne N, Trinchet JC, et al. Prospective study of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in Caucasian patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1994; 20: 65-71.

- 10. Peterson MS, Baron RL. Radiologic diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2001; 5: 123-144.

- 11. Liu WC, Lim JH, Park CK, et al. Poor sensitivity of sonography in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in advanced liver cirrhosis: accuracy of pre transplantation sonography in 118 patients. Eur Radiol 2003; 13: 1693-1698.

- 12. Zhang BH, Yang BH. Combined alpha fetoprotein testing and ultrasonography as a screening test for primary liver cancer. J Med Screen 1999; 6: 108-110.

- 13. Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2004; 130: 417-422.

- 14. Trevisani F, De NS, Rapaccini G, et al. Semiannual and annual surveillance of cirrhotic patients for hepatocellular carcinoma: effects on cancer stage and patient survival (Italian experience). Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 734-744.

- 15. Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005; 42: 1208-1236.

- 16. Lencioni R, Cioni D, Delia Pina C, et al. Imaging diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis 2005; 2: 162-170.

- 17. Lencioni R, Pinto F, Armillotta N, Bartolozzi C. Assessment of tumor vascularity in hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of power Doppler US and color Doppler US. Radiology 1996; 201: 353-358.

- 18. Rickes S, Schulze S, Neye H, et al. Improved diagnosing of small hepatocellular carcinomas by echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography in patients with cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 15: 893-900.

- 19. Tanaka S, Ioka T, Oshikawa O, et al. Dynamic sonography of hepatic tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177: 799-805.

- 20. d'Onofrio M, Martone E, Pozzi Mucelli R. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) in the screening of patients affected by chronic liver disease/cirrhosis. Poster Presentation 13th United European Gastroenterology Week, 2005, Copenhagen.

- 21. Quaida E, Calliada F, Bertolotto M, et al. Characterization of focal liver lesions with contrast-specific US modes and a sulfur hexafluori-de-filled microbubble contrast agent: diagnostic performance and confidence. Radiology 2004; 232:420-430.

- 22. Gaiani S, Celli N, Piscaglia F, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced perfusional sonography in the assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma hypervascular at spiral computed tomography. J Hepatol 2004; 41: 421-426.

- 23. Rickes S, Ocran K, Schulze S, Wermke W. Evaluation of Doppler so-nographic criteria for the differentiation of hepatocellular carcinomas and regenerative nodules in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ultraschall Med 2002; 23: 83-90.

- 24. Bhartia B, Ward J, Guthrie JA, Robinson PJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic livers: double-contrast thin-section MR imaging with pathologic correlation of explanted tissue. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 577-584.

- 25. Lutz AM, Willmann JK, Goepfert K, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: enhancement patterns at dynamic gadolinium- and su-perparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced Tl-weighted MR imaging. Radiology 2005; 237: 520-528.

- 26. Kim YK, Kwak HS, Kim CS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: comparison of SPIO-enhanced MR imaging and 16-detector row CT. Radiology 2006; 238: 531-541.

- 27. Stoker J, Romijn MG, de Man RA, et al. Prospective comparative study of spiral computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for detection off hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2002; 51: 105-107.

- 28. Colli A, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography, spiral CT, magnetic resonance, and alpha-fetoprotein in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: a systemic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:513-523.

- 29. Caturelli E, Solmi L, Anti M, et al. Ultrasound guided fine needle biopsy of early hepatocellular carcinoma complicating liver cirrhosis: a multicentre study. Gut 2004; 53: 1356-1362.

- 30. Caturelli E, Biasini E, Bartolucci F, et al. Diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma complicating liver cirrhosis: utility of repeat ultrasound--guided biospy after unsuccessful first sampling. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2002; 25: 295-299.

- 31. Bolondi L, Benzi G, Santi V, et al. Relationship between alpha-fetoprotein serum levels, tumour volume and growth rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in a western population. Ital J Gastroenterol 1990; 22: 190-194.

- 32. Toyoda H, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, et al. Prognostic significance of simultaneous measurement of three tumor markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006: 4: 111 117.

- 33. Koike Y, Shiratori Y, Sato S, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin as a useful predisposing factor for the development of portal venous invasion in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective analysis of 227 patients. Cancer 2001; 91: 561-569.

- 34. Yan P, Yan LN. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2003; 2:491-495.

- 35. Bigourdan JM, Jaeck D, Meyer N, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in Child A cirrhotic patients: hepatic resection versus transplantation. Liver Transpl 2003; 9: 513-520.

- 36. Giangregorio F, Aragona G, Marinone M, et al. Clinical utility of contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) for the control of loco-regional treatments of HCCs. Poster Presentation 13th United European Gastroenterology Week, 2005, Copenhagen.

- 37. Pompili M, Mirante VG, Rondinara G, et al. Percutaneous ablation procedures in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma submitted to liver transplantation: assessment of efficiacy at explant analysis and of safety for tumor recurrence. Liver Transplant 2005; 9: 1117-1126.

- 38. Chen YK, Hsieh DS, Liao CS, et al. Utility of FDG-PET for investigating unexplained serum AFP elevation in patients with suspected hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Anticancer Res 2005; 25: 4719-4725.

- 39. Bismuth H, Majno PE, Adam R. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liv Dis 1999; 19: 311-322.

- 40. Yao FY, Hirose R, LaBerge JM, et al. A prospective study on downsta-ging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 2005; 12: 1505-1514.

- 41. Peterson MS, Baron RL, Marsh JW Jr, et al. Pretransplantation surveillance for possible hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: epidemiology and CT-based tumor detection rate in 430 cases with surgical pathologic correlation. Radiology 2000; 217: 743-749.

- 42. Lim JH, Kim CK, Lee WJ, et al. Detection of hepatocellular carcinomas and dysplastic nodules in cirrhotic livers: accuracy of helical CT in transplant patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000; 175: 693-698.

- 43. Rode A, Bancel B, Douek P, et al. Small nodule detection in cirrhotic livers: evaluation with US, spiral CT, and MRI and correlation with pathologic examination of explanted liver. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2001; 25: 327-336.

- 44. de Ledinghen V, Laharie D, Lecesne R, et al. Detection of nodules in liver cirrhosis: spiral computed tomograpy or magnetic resonance imaging? A prospective study of 88 nodules in 34 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 159-165.

- 45. Libbrecht L, Bielen D, Verslype C, et al. Focal lesions in cirrhotic ex-plant livers: pathological evaluation and accuracy of pretransplantation imaging examinations. Liver Transp. 2002; 8: 749-761.

Pro přístup k článku se, prosím, registrujte.

Výhody pro předplatitele

Výhody pro přihlášené