Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma as a diagnostic challenge in a patient after anterior cervical fusion

Pavol Vigláš1,2, Eva Wittenbergerová3, Marek Ostrožlík4, Jan Raupach1, Patrik Matras2,5, Filip Cihlář2

+ Affiliation

Summary

Intramural esophageal hematoma is a well-described but rare condition of the esophagus. This condition can develop from a variety of causes and can be easily misdiagnosed even with a known medical history, especially in the unconscious patient. We present a rare case of spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma after recent anterior cervical fusion that was initially misdiagnosed as a cervical and mediastinal hematoma. Multiphase computed tomography, as well as upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and laboratory results, were essential for diagnosis and to avert unnecessary surgery.

Keywords

esophageal diseases, esophageal hematoma, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, mediastinal mass

Introduction

The condition known as intramural esophageal hematoma (IEH) is a rare form of esophageal disease characterized by a collection of blood within the wall of the esophagus. This unusual condition can develop from various causes, including trauma, severe vomiting, and endoscopic procedures, but it can also occur spontaneously. Some risk factors include pre-existing coagulopathy, older age, and female sex. Regardless of the cause, the clinical triad of retrosternal pain, painful swallowing (odynophagia) or difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), and vomiting blood (hematemesis) has been reported in about one third of patients.

Various diagnostic modalities have been used to identify this condition. Rapid identification by imaging modalities, particularly chest computed tomography (CT), has been shown to be critical for rapid and accurate diagnosis [1–3]. In addition, CT can exclude other thoracic pathologies such as aortic dissection, tumors, or pneumomediastinum. CT typically shows either symmetric or asymmetric thickening of the esophageal wall, accompanied by a distinct, non-enhancing, high-attenuation mass extending along the esophageal structure [4].

We present a rare case of spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma in a patient following recent anterior cervical fusion using the Caspar plating system. This condition was initially misdiag- nosed as cervical and mediastinal hematoma by an inexperienced radiologist. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma was confirmed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and laboratory results.

Case report

A 90-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a BMI of 33, diabetes mellitus type 2, diabetic nephropathy, arterial hypertension, peripheral and coronary artery disease, and hypothyroidism. Chronic daily medications were 100 mg acetylsalicylic acid, 125 mg levothyroxine, 300 mg allopurinol, and 2.5 mg bisoprolol together with oral diabetes medications. There was no history of major surgery. The patient lived with her grandson. The patient had chronic bilateral pleural effusions of unknown origin.

The patient was admitted to the regional hospital after a fall while trying to get up. Initial clinical findings included a scalp laceration, nosebleed, and quadriplegia. The family reported a history of chronic vertebral pain syndrome with a 6-month history of limited mobility, leaving the patient almost bedridden. A CT scan of the head and neck revealed severe osteochondrosis at the C5/6 segment, and a subsequent MRI showed complete stenosis and myelopathy in this area. The patient was recommended for microsurgical discectomy and anterior cervical fusion of the 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae using the Caspar plating system, and was then transferred to the trauma center. The operation was successful and the patient was moved back to the intensive care unit (ICU) of the regional hospital. Shortly after admission, the patient developed community-acquired pneumonia, which was initially treated empirically. Later, cultures identified Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Anticoagulation therapy was initiated with 0.8 mL of enoxaparin sodium (Clexane®, Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd) twice daily for the first episode of atrial fibrillation.

On the fifth day of therapeutic anticoagulation, a hematoma measuring 5 × 5 × 4.5 cm developed on the right side of the neck. Ultrasound showed the hematoma was heterogeneous, with no active leakage, and had a slight deviation of the trachea and blood vessels to the left. The surgeon performed an aspiration of the hematoma due to the risk of airway compression. The next day, the patient reported difficulty swallowing and worsening low back pain. There was no retrosternal pain or vomiting of blood. After the onset of symptoms, the vital signs were: blood pressure 163/66, heart rate 82 bpm, temperature 36.9 °C, and oxygen saturation 92%. An electrocardiogram showed known atrial fibrillation, and normal cardiac enzymes ruled out a heart attack. A nasogastric tube was inserted on the second attempt. Due to progressive respiratory failure, initial cyanosis, and a clinically increasing size of the cervical hematoma, intubation was performed.

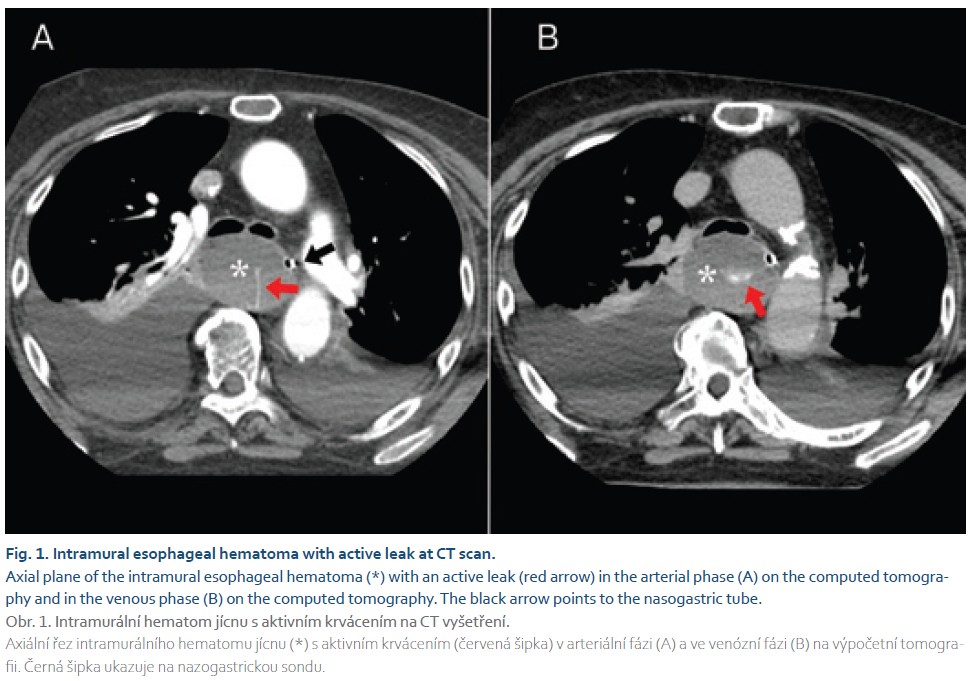

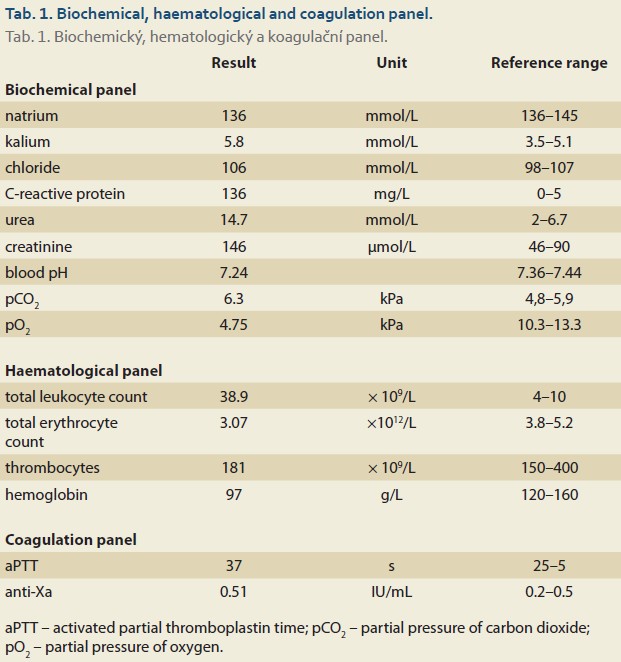

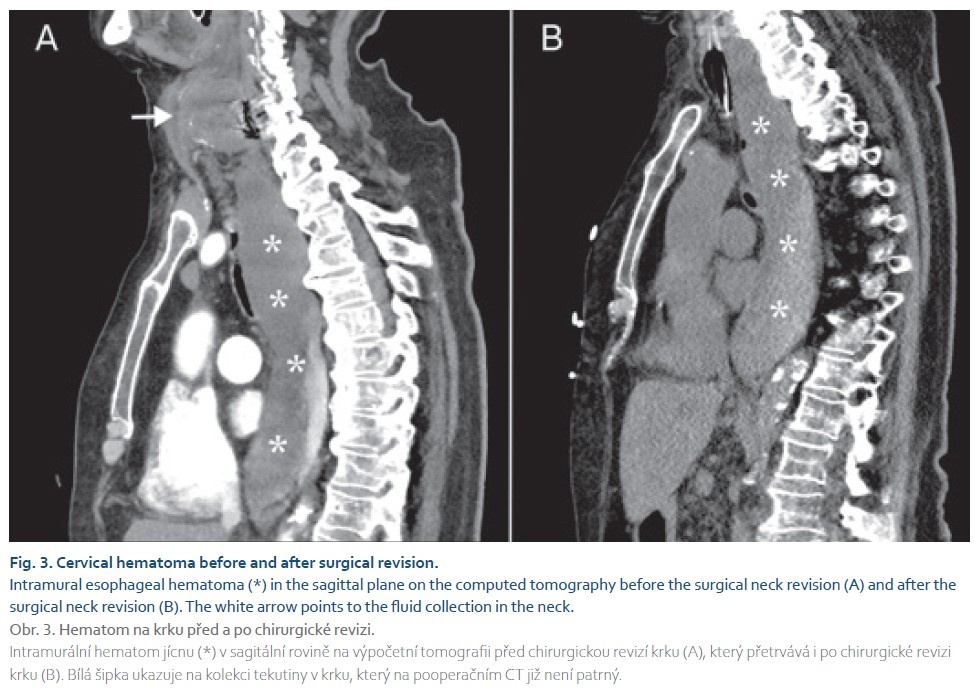

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest was performed as a four-phase study, including non-contrast, arterial, venous, and late-phase imaging at the regional hospital. The scan revealed fluid collection in the neck with low attenuation of 17 Hounsfield units (HU), non-enhancing, and measuring 7.5 × 4.5 × 3.8 cm near the surgical site. Another well-defined mass with higher attenuation of 40 HU in the non-contrast study and three active leaks in the arterial study was reported in the mediastinum. The mass was eccentric to the nasogastric tube, extending 2 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter to the diaphragm, with a total size of 4.3 × 5.3 × 4.9 cm. No fat stranding was found around the mass in the mediastinal fat. The regional hospital radiologist concluded that this was a cervico-mediastinal hematoma (Fig. 1). The patient’s history of the Caspar operation complicated the diagnostic process, so the postoperative cervical hematoma with progression into the mediastinum was initially considered as the most likely diagnosis. The neurosurgeon at the trauma center was contacted, and the patient was transferred back to the trauma center for surgery.

Labs upon admission to the trauma center showed high inflammatory markers (CRP 163 mg/L, leukocytosis 38.7 × 109/L)) and renal insufficiency (urea 14.7 mmol/L, creatinine 145 µmol/L, hyperkalemia 5.8 mmol/L). The patient had hypercapnic respiratory failure with a low pH (7.31). The blood count indicated low hemoglobin (97 g/L) and no thrombocytopenia. The coagulation profile showed an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) slightly above the upper limit of 40.8 s (upper limit is 35 s), but the anti--Xa level was still 0.51 IU/mL 15 hours after the last dose (therapeutic range is 0.5–1.2 IU/mL; prophylactic range is 0.2–0.5 IU/mL) (Tab. 1). Laboratory evidence of coagulopathy was found during treatment with enoxaparin, and antagonization with prothrombin complex and protamine was performed.

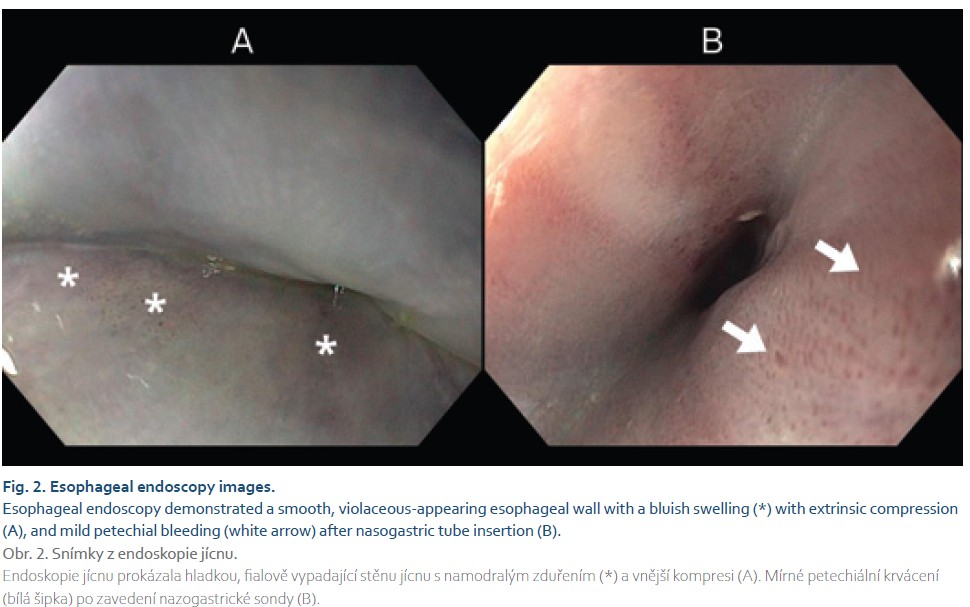

After an interdisciplinary consensus among the intensivist, neurosurgeon, thoracic surgeon, and radiologist at the trauma center, the findings suggested an intramural esophageal hematoma. However, the neck hematoma could be a postoperative complication that needed to be evacuated. The patient underwent a neck revision, revealing a clear fluid collection that did not communicate with the mediastinum. The clear collection resembled cerebrospinal fluid, but this was not confirmed biochemically. An upper GI endoscopy showed a circular bluish or purplish change in the mucosal color, indicating esophageal luminal compression along almost the entire length of the esophagus. The oral 3 cm of the esophagus and the gastroesophageal junction were not compressed. There was no evidence of mucosal tearing or esophageal perforation. Mild petechial hemorrhage was observed after the insertion of a nasogastric tube (Fig. 2).

The following day, after neck revision and upper GI endoscopy, an unenhanced CT of the neck and chest was performed. Examination showed an empty collection in the neck with a Redon drainage in place (Fig. 3). The size of the intramural esophageal hematoma didn‘t change, but after endoscopy a gas bubble was seen in the esophageal lumen, confirming the diagnosis of IEH. Conservative management of IEH was the method of choice. However, on the second day after readmission, the patient died of respiratory and renal failure.

Discussion

This rare case of intramural esophageal hematoma presents a diagnostic challenge in distinguishing it from mediastinal hematoma. Additionally, the spontaneous cause may be overlooked, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, along with laboratory results and CT images, must be evaluated by experienced physicians to accurately establish the diagnosis.

Half of the reported patients with IEH have two of the triad symptoms (retrosternal pain, odynophagia or dysphagia, and hematemesis), according to the current literature [1–7]. These factors cannot be assessed in the unconscious patient in the ICU. In these cases, we can rely on imaging techniques. The preferred primary diagnostic modality is multi-phase computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast. This non-invasive technique can be performed quickly and is available in most centers. A CT scan can demonstrate intraluminal or intramural soft tissue density and rule out esophageal perforation. The typical CT finding is a thickened esophageal wall with luminal compression or even obliteration of the lumen in large hematomas [7–10].

In our patient, the CT scan revealed a well-defined mass with smooth borders and typical hematoma attenuation of 40 HU, along with three active leaks indicating bleeding into the hematoma. There was no fat stranding around the hematoma, and the smooth borders suggested intramural esophageal hemorrhage. Both CT and endoscopy images showed compression of the esophageal lumen, confirmed by the nasogastric tube placed peripherally. The patient‘s history of Caspar surgery complicated the diagnostic process, as a cervical hematoma progressing into the mediastinum was considered the most likely diagnosis. However, the neck revision operation confirmed no communication between cervical collection and the mediastinal mass, and the intramural esophageal hemorrhage did not change size after draining the neck collection. Additionally, attenuation of the collections in the neck and mediastinum differed (17 vs. 40 HU), suggesting different causes. The etiology of the neck collection/hematoma remains unclear. However, we can confidently state that this was not a case of intramural esophageal hemorrhage as a surgical complication following the Caspar operation. Posterior mediastinal hematoma was included in the differential diagnosis, but since no mucosal tear in the esophagus was found during endoscopy and no communication with the cervical collection was identified during the neck revision, this diagnosis was ruled out.

Spontaneous IEH, as in our case, typically affects middle-aged or elderly women, often those on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy [4–6]. A primary intramural hemorrhage has been suggested as the cause, possibly due to underlying undetectable coagulation defects and anticoagulation therapy [3,6]. In our patient, anti-Xa levels remained within the prophylactic range even 15 hours after the last dose, indicating that they were likely in the therapeutic range at the time of symptom onset. The interdisciplinary team agreed on conservative management for our patient, which is recommended in the literature [3,7,8].

There have been reported cases of intramural esophageal hematomas due to various factors, such as trauma (including iatrogenic causes during nasogastric tube insertion or endoscopic procedures), foreign body ingestion, or severe vomiting [1–7]. Other rare causes of esophageal hematomas include food impaction, blunt abdominal trauma, and pill-related injuries [11–13]. Intramural hematomas of the esophagus can occur with or without a distinct mucosal tear. The hematoma may be concentric or eccentric, depending on its extent. All authors conducted a thoracic CT scan to rule out other emergencies, which typically revealed a slightly hyperattenuated longitudinal mass, similar to our case. In all reported cases, authors noted no enhancement after the injection of contrast medium. This makes our case report the first to document active bleeding into an intramural esophageal hematoma. In most cases, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a large obstructive blue lesion in the esophagus, as seen in our patient.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the diagnostic difficulties in the evaluation of neck and mediastinal hematomas in patients following recent neck surgery. Although rare, spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of dysphagia and chest pain, especially in patients with hypertension and anticoagulation therapy. Correct diagnosis by computed tomography and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy may avoid unnecessary surgery. An experienced radiologist is essential for a correct diagnosis.

ORCID authors

P. Vigláš 0009-0001-3380-0368,

J. Raupach 0000-0002-1529-2355,

P. Matras 0000-0002-5854-513X,

F. Cihlář 0000-0001-8139-4707.

Submitted/Doručeno: 5. 2. 2025

Accepted/Přijato: 6. 4. 2025

Corresponding author

Pavol Vigláš, MD

Department of Radiology

J. E. Purkyně University – Faculty of Health Studies

and Krajská zdravotní, a. s. – Masaryk Hospital

Sociální péče 3316/12

400 13 Ústí nad Labem

pavol.viglas@kzcr.eu

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Syed TA, Salem G, Fazili J. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16(2): e19–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.027.

2. Fasullo M, Patel K, Mehta S. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus: an unusual case of dysphagia and mediastinal mass. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112: 932.

3. Sadaniantz K, Thurber L, Petersile M. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the esophagus presenting with chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115: S1045–S1046. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000710048.77028.cb.

4. Cao DT, Reny JL, Lanthier N et al. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2012; 6(2): 510–517. doi: 10.1159/000341808.

5. Sharma A, Hoilat GJ, Ahmad SA. Esophageal hematoma. 2024 [online]. Available from: https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK4 59228/.

6. Enns R, Brown JA, Halparin L. Intramural esophageal hematoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51(6): 757–759. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.104350.

7. Meininger M, Bains M, Yusuf S et al. Esophageal intramural hematoma mimicking esophageal mass. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56(5): 767–770. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128650.

8. Li X, Liu L, Cao D et al. Spontaneous hematoma of posterior mediastinum with an uncommon cause: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Pract 2016; 6(1): 838. doi: 10.4081/cp.2016.838.

9. Suzuki K, Shiono S, Hayasaka K et al. A surgical case of mediastinal hematoma caused by a minor traffic injury. J Cardiothorac Surg 2020; 15(1): 12. doi: 10.1186/s13019-020-1065-x.

10. Glazer HS, Molina PL, Siegel MJ et al. High-attenuation mediastinal masses on unenhanced CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991; 156(1): 45–50. doi: 10.2214/ajr.156.1.1898569.

11. Klygis LM. Esophageal hematoma and tear from a taco shell impaction. Gastrointest Endosc 1992; 38(1): 100. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70359-9.

12. Rozec B, Rigal JC, Leteurnier Y et al. Post-traumatic hematoma of the esophagus. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1998; 17(9): 1160–1163. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(00)80013-1.

13. Piccione PR, Winkler WP, Baer JW et al. Pill-induced intramural esophageal hematoma. JAMA 1987; 257(7): 929.