Ileocaecal Crohn’s disease and familial adenomatous polyposis in one patient – a case report

Vladimír Čan1, Filip Marek1, Zdeněk Kala Orcid.org 1, Karolína Poredská2, Radek Kroupa Orcid.org 3, Eliška Tvrdíková4, Tomáš Andrašina Orcid.org 5, Vladimír Procházka Orcid.org 1, Lumír Kunovský1,2

+ Affiliation

Summary

Crohn’s disease (CD) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) are two different diseases that both affect the gastrointestinal tract. FAP is an autosomal dominant inherited disease; however, the aetiology of CD is still unknown and is supposed to be multifactorial (genetics, environment, immune state, microbiom). The therapy of these two diseases differs as well. The ultimate solution for FAP is surgery (colectomy or proctocolectomy). On the other hand, CD can be treated either conservatively or surgically. Generally, in cases of bowel resection, the alternative of gastrointestinal tract restoration has to be considered. This decision is more challenging in patients diagnosed with both diseases (CD and FAP). We present the case of a young female with FAP who was diagnosed with active CD in the ileocaecal region. Due to multiple large colon polyps and a stenotic terminal ileum, she was indicated for surgery (colectomy with terminal ileostomy and terminal ileum resection). Subsequently, an ileorectal anastomosis was constructed. In further text, we also discuss other bowel restoration solutions, such as ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and abdominoperineal resection with terminal ileostomy.

Keywords

Crohn’s disease, J-pouch, familial adenomatous polyposis, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, ileorectal anastomosis, colectomy, bowel continuity restorationIntroduction

Familiar adenomatous polyposis

Familiar adenomatous polyposis (FAP, also adenomatous polyposis coli – APC) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease with incidence varying from 1/7 000 to 1/22 000. The cause of FAP is a mutation of the APC gene localised on the long branch of the 5th chromosome. The APC gene is a tumour suppressor gene responsible for transcription and translation of the APC protein and its mutation can lead to colorectal and other cancer [1].

The classic form of FAP is characterised by a large number (up to thousands) of adenomatous colon polyps. The typical onset of FAP is in early adolescence. If not treated, polyps can become malignant. The colorectal cancer is then diagnosed approximately at the age of 39. There are only case reports of detection of malignant polyps in children with FAP [2].

The attenuated form of FAP (AFAP – attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis) is described only in 8% of families affected by FAP. This variation of FAP is characterised by a smaller number of less malignant polyps. The AFAP is therefore diagnosed much later than classic FAP – at the age of around 55 [3].

Treatment of FAP

The management of FAP is based on identifying the patients at risk (family history, genetic testing) and introducing their close monitoring. The method of choice for an early polyp detection is a colonoscopy. The removal of any polyp found is necessary to prevent the development of colorectal cancer [4]. Specific pharmacologic treatment of FAP is not yet available. However, several studies consider the cyclooxygenase blockers as a promising treatment of FAP [5,6].

In FAP with advanced dysplastic polyps, endoscopically non-removable lesions or more than 100 polyps, the method of choice is a prophylactic colectomy [7]. This radical procedure minimises the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Nowadays, there are no specific recommendations for bowel continuity restoration after colonic resections [8]. The decision for performing either colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) should be individually based with consideration of the presence of rectal polyps [9]. The proctocolectomy is usually performed in patients with more than 20 rectal polyps, if the polyps are larger than 3 cm or if there are malignant changes [10]. The laparoscopic approach is the method of choice as it ensures lower morbidity and faster postoperative recovery [11].

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease which may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. However, in up to 1/3 of cases the disease is localised in the ileocaecal region [12].

The aetiology of CD is still unknown and therefore a causal therapy is not yet available. Concerning the pathogenesis of CD, it is nowadays believed to be multifactorial and genetics probably play an important role in its development. The most frequently mentioned gene mutation is the NOD2/CARD15 that is significantly higher in CD patients than in the healthy population [13,14]. However, it is not the only pathognomonic gene mutation in CD development. Hence, the genetic testing is currently not recommended for routine diagnosis of CD [15].

Treatment of ileocaecal Crohn’s disease

Patients with localised ileocaecal disease can be treated either conservatively or surgically mainly according to the disease activity and the presence of obstructive symptoms due to stenosis.

In mildly or moderately active disease, local or systemic corticosteroids should be considered. In severely active CD, the patients should also be initially treated with systemic corticosteroids. However, for all patients who relapse (who are steroid-refractory or steroid-intolerant) an anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha based strategy is appropriate.

Surgery is an alternative for patients with disease refractory to conventional medical treatment or in patients with obstructive symptoms but with no significant evidence of active inflammation. The laparoscopically-assisted ileocaecal resection with wide-lumen stapled ileocolic side to side anastomosis is the preferred technique [16,17].

In patients with a concomitant abdominal abscess, management should start with antibiotics, percutaneous or surgical drainage, followed by delayed resection, if necessary [15,18,19].

Case report

We present the case of a 24-year-old female who was referred to our hospital by a general practitioner for a 4-week lasting abdominal pain, occasionally vomiting and a palpable mass in the right iliac fossa. On examination she was slightly leaning forward when walking, her abdomen was a little distended and the mass in the right iliac fossa was approximately 8 × 4 cm large and painful on deep palpation. The laboratory findings were normal, including the markers of inflammation and the abdominal ultrasound revealed periappendicular infiltration, advanced inflammatory changes in the subcaecal region with a suspicion of an acute appendicitis. She was therefore admitted to our department of surgery.

Concerning her past medical history, she was diagnosed with FAP according to the colonoscopy and genetic results (mutation in APC gene c.2434-2437delGACA p.Asp812fsX7) a few years previously. The last colonoscopy (performed 4 months earlier in a different hospital) showed multiple large intestinal polyps, no biopsies were taken and the terminal ileum was not examined. In her family, her grandmother and mother were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and two of her siblings with FAP. She was not using any medication and stated no allergies.

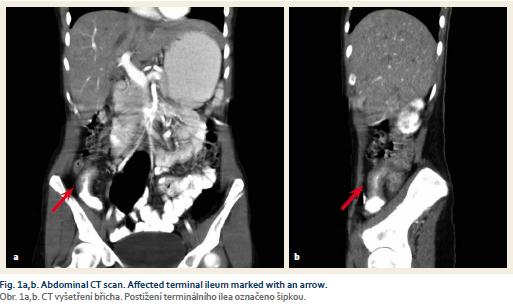

With regards to a possible differential diagnosis (appendicitis, CD) the CT scan was performed and showed inflammatory changes in the ileocaecal region, stenosis of the terminal ileum, a 6 cm long thickening of ileal wall and surrounding lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1a,b). With close cooperation with a gastroenterologist, a conservative approach was indicated. She was treated with antibiotics (metronidazole) and started bowel rest by means of intravenous parenteral nutrition. To confirm the diagnosis of CD a colonoscopy was performed. It revealed stenosis of the ileocaecal valve that enabled only a short intubation of the terminal ileum. There were no signs of macroscopic inflammation either at the ileocaecal valve or the terminal ileum. However, the biopsy from the terminal ileum showed histopathological signs of CD. As the patient repetitively showed obstructive symptoms due to stenosis of the terminal ileum, we decided not to treat her with corticosteroids but indicated her for ileocaecal resection.

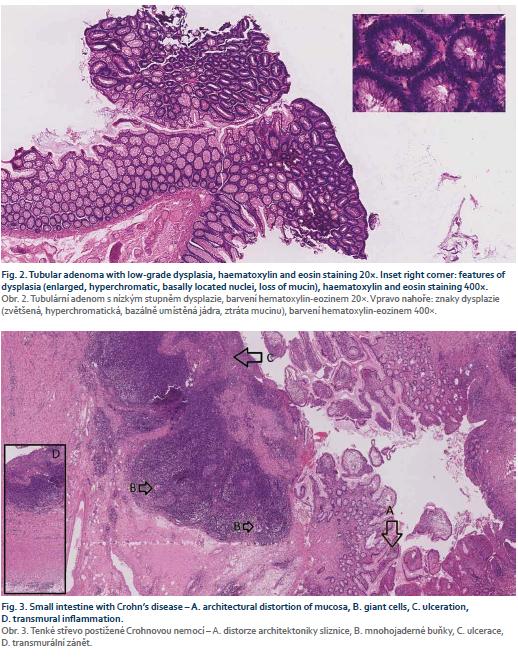

Concerning the FAP, the colonoscopy revealed multiple large colonic polyps with low-grade dysplasia adenomas on biopsy. Particularly in the rectum, there were approximately 10 polyps up to 5 mm in size.

Consequently, after a discussion within a multidisciplinary team (surgeons, gastroenterologists and radiologists) it was recommended for the patient to undergo a colectomy with a resection of the terminal ileum and construction of the neoterminal ileostomy at the same time. The procedure was performed laparoscopically with no complications per-or postoperatively and the patient was soon discharged. A definitive histopathologic examination of the resected colon confirmed low-grade adenomas (Fig. 2) and the examination of the terminal ileum showed signs of CD (Fig. 3).

The patient has been regularly seen by a gastroenterologist and treated with azathioprine as a prophylaxis after a surgically induced remission of CD. As far as the bowel restoration is concerned, after 18 months the ileorectal anastomosis was performed without any complication. Regarding the FAP, the remaining rectal polyps were endoscopically removed, and the histology confirmed low-grade adenomas. Nevertheless, the patient has to undergo regular endoscopies of the rectum in order to detect early rectal cancer. The last endoscopy of the rectal stump showed no polyps and the patient is currently doing well without any health problems.

Discussion

CD and FAP are both diseases that affect the gastrointestinal tract, however the treatment management of the diseases is different. Concerning CD, the treatment can be either conservative or surgical. As CD can affect the whole gastrointestinal tract, any surgery performed is always a bowel saving surgery to prevent short bowel syndrome. On the other hand, the only surgical treatment of FAP is colectomy or proctocolectomy as a prophylaxis of a malignant transformation or a cancer development.

The therapeutic dilemma appears if both diseases occur in one patient as described in our case report. Our patient was indicated for the ileocaecal resection due to CD and obstructive symptoms and at the same time she was indicated for colectomy due to FAP and multiple large polyps. The possibilities of bowel continuity restoration had to be discussed with the patient well in advance.

In the literature, there is a lack of patients diagnosed with CD and FAP and almost no recommendations concerning the most convenient type of bowel continuity procedure in these patients [20–22]. Moreover, these case reports refer to patients who were diagnosed with CD just after the proctocolectomy with IPAA due to FAP. In our case the patient with FAP was diagnosed with CD even before any surgery.

A standard procedure to connect the ileum and the anal stump after proctocolectomy is creating an IPAA. At our department we construct a standard J-pouch from the terminal ileum connected to the anal canal. In the last 10 years, we have performed this procedure in 5 patients with FAP and in 45 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

When planning a bowel continuity restoration in a patient with FAP and CD after colectomy with ileocaecal resection, the following options have to be considered:

1. Finishing proctectomy and creating IPAA

-

a gold standard after colectomy in patients with FAP or UC;

-

disadvantage: not suitable in CD – construction of J-pouch using ileum as the most common location of CD constitutes a high-risk relapse of CD. Some authors consider CD of terminal ileum as a contraindication for J-pouch construction [23–25].

2. Ileorectal anastomosis

-

suitable for patients with a colonic form of CD;

-

disadvantage: leaving the rest of the rectum represents almost a 100% certainty of developing a rectal cancer in FAP patient in later life.

3. Abdominoperineal resection with terminal ileostomy

-

a definitive and ultimate solution for FAP and CD patients as well;

-

disadvantage: a devastating irreversible procedure in a young patient without proof of malignity.

According to our opinion, in patients with FAP and CD, the most suitable solution for a bowel continuity restoration is to construct an ileorectal anastomosis. However, provided that the rectum is well preserved, the rectal polyps can be treated endoscopically with no signs of malignancy and there are no signs of active CD. The ileorectal anastomosis preserves the patient’s anal sphincter and rectum and gives the patient a chance not to have a terminal ileostomy for the rest of the life. Moreover, the rectal stump is easy for endoscopic detection of the polyps.

On the other hand, in the case of severe findings (multiple, large polyps, malignant changes or active CD) in the rectum, the abdominoperineal resection and construction of a terminal ileostomy should be performed.

Concerning the possibilities of a bowel continuity restoration in our patient, a comprehensive discussion with the patient was performed, explaining the pros and cons of all the alternatives. She finally decided to undergo a bowel continuity restoration with ileorectal anastomosis. However, we have to keep in mind that only a total proctocolectomy would minimise the risk of a rectal cancer development in a patient with FAP.

Conclusion

CD and FAP are two different diseases affecting the gastrointestinal tract and the course of the treatment also varies. In the literature, there are very few cases describing FAP and CD in one patient. In case of need for colectomy due to FAP and ileocaecal resection due to CD at the same time, the decision of possibility bowel continuity restoration might be demanding. In our case report, we present ileorectal anastomosis as a well-balanced solution for bowel continuity restoration. However, the patient needs to undergo a careful endoscopic surveillance in order to detect an early rectal cancer.

Supported by Ministry of Health, Czech Republic – conceptual development of research organi-sation (FNBr, 65269705).

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE „uniform requirements“ for biomedical papers.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Submitted/Doručeno: 4. 11. 2018

Accepted/Přijato: 24. 1. 2019

Lumir Kunovsky, M.D., Ph.D.

Department of Surgery

University Hospital Brno

Jihlavska 20

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

lumir.kunovsky@gmail.com

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Galiatsatos P, Foulkes WD. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101 (2): 385–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00375.x.

2. Durno C, Aronson M, Bapat B et al. Family history and molecular features of children, adolescents, and young adults with colorectal carcinoma. Gut 2005; 54 (8): 1146–1150. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.066092.

3. Knudsen AL, Bisgaard ML, Bülow S. Attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis (AFAP). A review of the literature. Fam Cancer 2003; 2 (1): 43–55.

4. Vasen HF, Griffioen G, Offerhaus GJ et al. The value of screening and central registration of families with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum 1990; 33 (3): 227–230.

5. Lynch PM, Burke CA, Phillips R et al. An international randomised trial of celecoxib versus celecoxib plus difluoromethylornithine in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut 2016; 65 (2): 286–295. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307235.

6. Samadder NJ, Neklason DW, Boucher KM et al. Effect of sulindac and erlotinib vs placebo on duodenal neoplasia in familial adenomatous polyposis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315 (12): 1266–1275. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2522.

7. Schneider R, Schneider C, Dalchow A et al. Prophylactic surgery in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) – a single surgeon’s short-and long-term experience with hand-assisted proctocolectomy and smaller J-pouches. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015; 30 (8): 1109–1115. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2223-9.

8. Landerholm K, Abdalla M, Myrelid P et al. Survival of ileal pouch anal anastomosis constructed after colectomy or secondary to a previous ileorectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis patients: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017; 52 (5): 531–535. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1278457.

9. Tajika M, Niwa Y, Bhatia V et al. Risk of ileal pouch neoplasms in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19 (40): 6774–6783. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6774.

10. Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A et al. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Gut 2008; 57 (5): 704–713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136127.

11. Huang JL, Zheng ZH, Wei HB et al. Laparoscopic total colectomy and proctocolectomy for the treatment of familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8 (6): 9173–9176.

12. Loftus EV Jr, Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn’s disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16 (1): 51–60.

13. Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 2001; 411 (6837): 603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114.

14. Kunovsky L, Kala Z, Marek F et al. The role of the NOD2/CARD15 gene in surgical treatment prediction in patients with Crohn‘s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019; 34 (2): 347–351. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3122-7.

15. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11 (1): 3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168.

16. Bemelman WA, Warusavitarne J, Sampietro GM et al. ECCO-ESCP Consensus on Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12 (1): 1–16. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx061.

17. Simillis C, Purkayastha S, Yamamoto T et al. A meta-analysis comparing conventional end-to-end anastomosis vs. other anastomotic configurations after resection in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50 (10): 1674–1687. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9011-8.

18. Schoepfer AM, Dehlavi MA, Fournier N et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with a complicated disease course and increased operation rate. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108 (11): 1744–1753. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.248.

19. Kosmidis C, Anthimidis G. Emergency and elective surgery for small bowel Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol 2011; 15 (Suppl 1): S1-S4. doi: 10.1007/s10151-011-0728-y.

20. Fidalgo C, Ferreira S, Rosa I et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis and Crohn’s disease in one patient: dilemmas and concerns. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2013; 7 (2): 358–362. doi: 10.1159/000354972.

21. Fukushima K, Funayama Y, Shibata C et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis complicated with Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2006; 21 (7): 730–731. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0161-2.

22. Gentile N, Kane S. Onset of Crohn’s disease post-proctocolectomy for Familial Adenomatous Polyposis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17 (Suppl 2): S51. doi: 10.1097/00054725-201112002-00161.

23. Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg 1995; 222 (2): 120–127.

24. Turina M, Remzi FH. The J-pouch for patients with Crohn’s disease and indeterminate colitis: (when) is it an option? J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18 (7): 1343–1344. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2498-0.

25. van Duijvendijk P, Vasen HF, Bertario L et al. Cumulative risk of developing polyps or malignancy at the ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3 (3): 325–330.