Groove (paraduodenal) pancreatitis – a case series of six patients

Martin Kliment Orcid.org 1, Petr Fojtík Orcid.org 2, Martin Straka Orcid.org 3, Martin Loveček Orcid.org 4, Dušan Žiak Orcid.org 5, Pavol Holéczy Orcid.org 6,7, Ondřej Urban Orcid.org 8,9, Jaroslav Krátký Orcid.org 10

+ Affiliation

Summary

Groove pancreatitis (GP) is a special form of chronic pancreatitis characterised by the development of inflammatory changes and fibrous tissue formation in the ‚groove‘ between the pancreatic head, duodenum and common bile duct. Imaging studies show a mass in the groove close to minor papilla, a thickening, or cyst formations in the groove or the duodenal wall. Clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, weight loss or vomiting. The disease may imitate pancreatic head cancer, bile duct cancer or duodenal cancer, and its differentiation from pancreatic head carcinoma may be difficult. Conservative treatment alone or in combination with endoscopy is often successful. Surgery is indicated if conservative treatment fails or if carcinoma cannot be ruled out. Authors present their own experience with groove pancreatitis on a series of six patients diagnosed and treated at a single tertiary referral gastroenterology centre over a period of six years.

Keywords

chronic pancreatitis, endosonography, pancreatic cancer, paraduodenal pancreatitis, groove pankreatitisIntroduction

Groove pancreatitis (GP, also known as paraduodenal pancreatitis) is a special form of chronic pancreatitis characterised by the development of inflammatory and fibroproductive changes in the anatomical area of the ‚groove‘ between the pancreatic head, duodenum and common bile duct. Clinical symptoms and morphology can be identical to those of pancreatic head carcinoma. Nevertheless, with knowledge of the entity, certain clinical and morphological signs can be used to differentiate GP from pancreatic head carcinoma.The condition was first described by Becker [1] in 1973 and the term ‚groove pancreatitis‘ was introduced by Stolte in 1983 to indicate pancreatitis characterised by fibrous scars in the anatomical space between the dorsocranial section of the pancreatic head, duodenum and common bile duct [2]. Becker and Mischke subdivided GP into ‚pure‘ and ‚segmental‘ form [3]. In the pure form of GP, changes are localised in the groove only, between the duodenal wall and the pancreatic head, without affecting the pancreatic parenchyma or the main pancreatic duct. In the segmental form, in addition to those in the groove, changes are also present in the adjacent parenchyma of the pancreatic head, affecting (stricturing) the pancreatic duct or the common bile duct, too. Fléjou et al described this condition in a series of patients as a “cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas in the wall of the stomach or the duodenal wall” [4]. Adsay and Zamboni proposed the term ‚paraduodenal pancreatitis‘ [5]. Due to the frequent presence of cysts in the duodenal wall or in the groove in the pure form, and the presence of a mass in the segmental form, some authors prefer the terms cystic and solid form. The exact prevalence of GP is unknown. In three published studies, GP was present in 2.7%, 19.5% and 24.4% of resected tissue obtained by hemi‑duodenopancreatectomy in patients with chronic pancreatitis [2,3,6]. Despite the apparently ‚high‘ incidence of GP in the last two of the above mentioned studies, it is a condition that is rarely clinically diagnosed, as attested by only six patients identified in the authors‘ centre over six years.

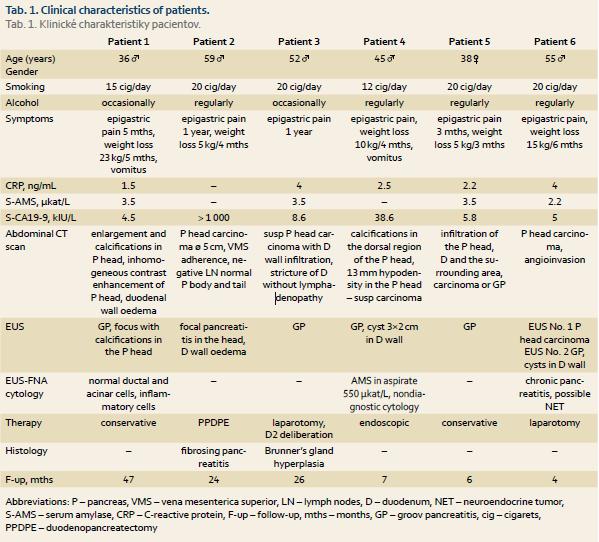

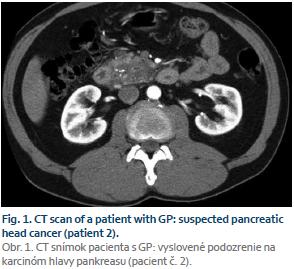

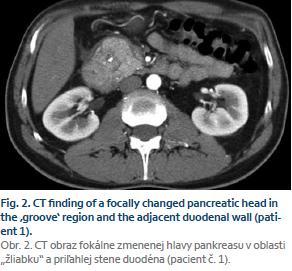

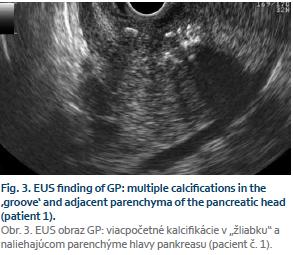

A case series of six patients

Over a period of six years we have diag- nosed and treated six patients with groove pancreatitis in our tertiary gastroenterology centre. Three patients underwent surgery, with diagnosis confirmed histologically; the remaining three were diagnosed on the basis of history, imaging examinations and clinical development. The patients’ clinical characteristics are detailed in Tab. 1. Their mean age (± SD) was 47.5 ± 9.4 years. Abdominal pain and weight loss were the most common clinical symptoms. Based on the contrast enhanced computer tomography (CT) examinations, pancreatic head carcinoma (Fig. 1) was suspected in five out of the six patients, while the benign changes, corresponding to pancreatitis (Fig. 2) were described by the radiologist in only one patient. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed focal pancreatitis with calcifications in the head (Fig. 3) and intact parenchyma and duct in the rest of the gland (Fig. 4) in all patients. Also showing on endoscopic ultrasound was a thickened duodenal wall in all patients, and cysts in the duodenal wall or in the so‑called groove in four patients (Fig. 5). EUS‑guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS‑FNA) was performed in three patients, with either non‑diagnostic cytology (n = 1, duodenal cyst aspiration) or confirming normal pancreatic and inflammatory cells (n = 2). The duodenal cyst aspiration showed a significant increase in amylase activity (1,852 µkat/L) and low levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA: 10.8). On the basis of the EUS scans, all patients were diagnosed with groove pancreatitis. Three patients underwent surgery. Proximal pylorus‑preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPDPE) was performed on the first patient, a deliberation of duodenum with intraoperative biopsy of the duodenal mucosa in the second, and laparotomy with intraoperative USG scan in the third. Histology confirmed fibrosing pancreatitis in the first patient and Brunner’s gland hyperplasia in the second. Patient four underwent two EUS‑guided duodenal cyst evacuations. Due to relapsing cyst in the duodenal wall with epigastric pain, EUS‑guided cystoduodenostomy (EUS‑CDS) was finally performed by introducing a pigtail drain into the duodenal cyst (Fig. 6). This patient continues to receive endoscopic treatment for distal common bile duct stricture by means of multi‑stenting, i.e. parallel introduction of several plastic duodenobiliary drains. All patients are followed-up by a gastroenterologist on an out‑patient basis and show favourable clinical development, characteristic of a benign condition of the pancreas. The mean length of follow‑up of the patients in the group was 19.0 ± 16.4 (SD) months.Discussion

Groove pancreatitis presents a conside-rable diagnostic problem, given that both its clinical picture and imaging exa- minations are very similar to pancrea- tic head carcinoma. The disease most commonly occurs in men aged 40–50 with a history of alcohol abuse and smo-king. Its pathogenesis is unclear. The pro- posed predisposing factor for the development of GP is the incomplete in- volution of dorsal pancreas with embryo-nic remnants of pancreas glands present in the duodenal wall or possibly ectopic pancreas in the duodenal wall [5]. Chronic alcoholism as a potentiating factor may increase pancreatic juice viscosity, lead to Brunner’s gland hyperplasia and cause minor papilla occlusion or dysfunc- tion [7,8]. The condition is often associat- ed with pancreas divisum, a narrowing or absence of the duct of Santorini [9].The most common clinical symptoms include abdominal pain and weight loss. In case of duodenal obstruction due to oedema of the duodenal wall, patients develop relapsing vomiting. Obstructive icterus is present if the pancreatic head is affected, with common bile duct stricture. Abdominal pain and weight loss was dominant in all patients in our series, with one patient loosing up to 23 kg, more suggestive of an advanced malignant condition rather than focal chronic pancreatitis.

Serum pancreatic enzymes activity is usually normal or slightly elevated, but never reaches levels as high as in acute pancreatitis. Tumor marker – carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbonic anhydrase 19-9 (CA 19-9) – levels usually fall within the normal range. Half of the patients in our set had elevated serum CA 19-9 levels, which in one patient reached the value of 1,000 – typical for pancreatobiliary malignancies.

Imaging techniques – contrast CT scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and EUS – are used to diagnose GP. The CT scan finding of the pure form of GP includes a hypodense lesion with delayed contrast enhancement between the duodenal wall and the pancreas near minor papilla, duodenal stricture with a widened duodenal wall, and a cyst in the duodenal wall or the adjacent part of the pancreatic head. Cysts may be small or large, and multilocular cystic ‚masses‘ also tend to occur. In the segmental form of GP, CT scan shows the presence of a hypodense mass in the pancreatic head near the duodenal wall, usually accompanied by the signs of advanced chronic pancreatitis with calcifications in the head around the minor papilla, stricture of the distal part of the pancreatic duct or common bile duct [3].

Distinguishing an adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head in the groove area (groove adenocarcinoma) from GP is difficult. The absence of cysts in the duodenal wall and frequent sparing of the pancreatic duct in groove adenocarcinoma may be helpful in the diag- nostic process [10]. Forceps biopsy from duodenal mucosa may contribute to a correct diagnosis but unless the groove adenocarcinoma invades the duodenal wall, establishing the correct diagnosis is a challenge. The finding of groove pancreatitis does not rule out a concomitant presence of adenocarcinoma. A markedly widened main pancreatic duct in combination with a mass in the groove area points to suspected groove adenocarcinoma. In contrast to adenocarcinoma, peripancreatic blood vessels are mostly intact in GP, without signs of thrombosis or infiltration. Despite advanced imaging techniques, it is often impossible to rule out carcinoma completely and unambiguously, and a large number of patients with GP undergo surgical resection [6]. In addition to carcinoma of the pancreas, common bile duct carcinoma and duodenal carcinoma must also be ruled out. Acute pancreatitis with periduodenal phlegmon or an acutely exacerbated chronic pancreatitis with a pseudocyst in the duodenal wall can also imitate the pure form of GP. In autoimmune pancreatitis, diffuse enlargement of the entire pancreas (‚sausage‑like‘ pancreas) and hypodense capsule around the pancreas are often present, in contrast to GP. Cysts in the pancreas or the duodenal wall and isolated involvement of the ‘groove’ area do not occur in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. In four out of five patients in our series, the diagnosis of suspected pancreatic head carcinoma was established on the basis of contrast CT examination and, consequently, three of the patients underwent surgical therapy.

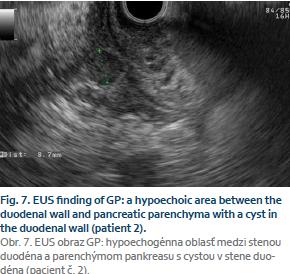

In an endosonographic examination, GP manifests as a hypoechoic area between the duodenal wall and pa-renchyma of the pancreas (Fig. 7); in the cystic form, cysts are usually present in the groove or in the duodenal wall, while in the solid form there is usually a solid mass in the periampullary region of the pancreatic head, with focal calcifications near minor papilla. In order to arrive at a more specific diagnosis, EUS‑FNA from a mass or a forceps biopsy from the macroscopically altered duodenal mucosa may be performed. When interpreting the results of cyto-logy obtained from EUS‑FNA, or the results of histology obtained from the forceps biopsy of the duodenum, it is important to bear in mind that a negative cytology or histology, or the presence of fibrosis in histology from forceps biopsy, does not rule out the presence of carcinoma (fibrosis may be the result of a desmoplastic reaction at the periphery of the carcinoma). In our set of patients, four out of five were diagnosed with GP on the basis of EUS examination. In patient six, pancreatic head carcinoma was suspected after the first EUS examination. Due to ambiguous cytology results (suspected NET), CT scan and the EUS finding of a mass in the pancreatic head, surgery was scheduled. However, findings obtained with laparotomy and intraoperative ultrasonography did not correspond with either carcinoma or NET, and resection was not performed. A control EUS examination four weeks after laparotomy showed the presence of the characteristic features of paraduodenal pancreatitis, including a cyst in the duodenal wall.

Distal common bile duct stricture, which may occur in some patients with GP, has a characteristic benign appearance in the cholangiogram, with regular smooth edges and a conical shape. Its correct interpretation may help to distinguish it from malignant common bile duct stricture in pancreatic head carcinoma.

The hypoechoic thickening of the duodenal wall, and the presence of one or more cysts in the duodenal wall or the groove, can be regarded as the most specific EUS sign of GP. Despite an EUS finding of GP, two more patients in our series underwent surgery, as pancreatic head carcinoma could not be ruled out completely (suspected CT finding, high serum CA19-9 levels).

Several approaches can be implemen-ted in the treatment of GP, depending on the nature and the course of the disease. A successful treatment essentially requires the elimination of risk factors, i.e. alcohol abuse and smoking. Acute flare‑ups of the disease are treated conservatively, in the same way as acute pancreatitis. The treatment consists of bed rest, discontinuation of intake per os, intravenous administration of crystalloid infusions, enteral or parenteral nutrition, and administration of analgesics. In our series of patients, patient one was successfully treated in this way. In cases of the much more common chronic relapsing course of the disease, which imitates the course of chronic pancreatitis, pharmacotherapy is used (analgesics, pancreatic enzymes if signs of exocrine insufficiency are present), along with endoscopic techniques for duodenal cyst drainage, transpapillary drainage in case of stricture of the duct of Wirsung or the duct of Santorini [11], or duodenobiliary drainage in case of common bile duct stricture. According to literary data, the success rate of endoscopic therapy is up to 70% [12].

The non‑standard endoscopic trans- duodenal drainage of a cyst in the duodenal wall in patient four merits a more detailed comment. The treatment was indicated due to persisting abdominal pain; a stricture was present in the duodenum and after two EUS‑guided aspirations the cyst relapsed. Reports on this treatment in global literature are limited. According to Arvanitakis et al [12], out of the total of 39 patients with paraduodenal pancreatitis who received endoscopic treatment, only 17 underwent endoscopic cystoduodenostomy as part of the initial treatment, and another four as part of re‑treatment due to relapsing symptoms. The authors do not specify whether the cystoduodenostomy involved a cyst in the duodenum or the pancreatic head, but given the number of patients diagnosed with one (n = 17) or more (n = 9) cysts in the duodenal wall, it may be inferred that they were referring to duodenal cysts. The treated cysts included cysts < 3cm in size, which is similar to our case [12].

Surgical therapy is indicated when conservative or endoscopic therapy is unsuccessful, or when carcinoma cannot be reliably ruled out.

In our series of patients, 50% under-went surgery, one patient (16.7%) re-ceived endoscopic treatment, and two (33.3%) were treated conservatively. Due to the limited number of papers published, the small number of patients in cohorts, and the retrospective nature of studies, it is difficult to evaluate the share of various therapies in the mana-gement of patients with GP. In the largest retrospective study published to date of 51 symptomatic, radiologically diagnosed GP patients, 19 (37.3%) initially received conservative pharmacological treatment, 39 (76.5%) initially re-ceived only endoscopic treatment in combination with pharma-cotherapy, and three (5.9%) underwent urgery [12].

Conclusion

GP is a special form of a focal chronic pancreatitis affecting the anatomical region of the ‚groove‘ between the pancreatic head, duodenal wall and common bile duct. Both its clinical picture and imaging studies are very similar to pancreatic head carcinoma, making it difficult to diagnose. A contrast CT scan is not accurate enough to diagnose GP, and in our ground of patients only 17% were diagnosed correctly based on the CT scans. Endosonography is of significant help in the diagnostic process, and the presence of one or more cysts in the duodenal wall or in the groove, together with a hypoechoic thickening of the groove and adjacent duodenal wall, can be regarded as the most specific EUS signs of GP.Depending on the patient‘s clinical conditions and on how reliably the con- dition was diagnosed, GP management involves conservative approach, endo-scopic therapy, or surgical procedures. Even with sufficient knowledge of the diagnosis, half of the patients in our set underwent surgery because carcinoma could not be reliably ruled out. In order to be diagnosed correctly, the condition requires not just the availability of all imaging methods, including the EUS, but also sufficient awareness by the gastroenterologists, radiologists and surgeons of this clinical entity.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE „uniform requirements“ for biomedical papers.

Submitted/Doručeno: 11. 1. 2015

Accepted/Přijato: 6. 4. 2015

MUDr. Martin Kliment, Ph.D.

Digestive Disease Center

Hospital Vítkovice, Ostrava

Zalužanského 1192/15

703 84 Ostrava-Vítkovice

martin.kliment@nemvitkovice.cz

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Becker V. Bauchspeicheldrüse. In: Doerr W, Seifert G, Thlinger E (eds). Spezielle pathologische Anatomie. 4th ed. Berlin/Heidelberg/New York: Springer 1973: 252–445.

2. Stolte M, Weiss W, Volkholz H et al. A special form of segmental pancreatitis: „groove pancreatitis“. Hepatogastroenterology 1982; 29 (5): 198–208.

3. Becker V, Mischke U. Groove pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol 1991; 10 (3–4): 173–182.

4. Fléjou JF, Potet F, Molas G et al. Cystic dystrophy of the gastric and duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: an unrecognized entity. Gut 1993; 334 (3): 343–347.

5. Adsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico‑pathologically distinct entity unifying „cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas“, „para‑duodenal wall cyst“ and „groove pancreatitis“. Sem Diagn Pathol 2004; 21 (4): 247–254.

6. Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M. Groove pancreatitis masquerading as pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Surg 1992; 163 (3): 312–316.

7. Chatelai, D, Vibert E, Yzet T et al. Groove pancreatitis and pancreatic heterotopia in the minor duodenal papilla. Pancreas 2005; 30 (4): e92–e95.

8. Malde DJ, Oliveira‑Cunha M, Smith AM. Pancreatic carcinoma masquerading as groove pancreatitis: case report and review of literature. JOP 2011; 12 (6): 598–602.

9. Shudo R, Obara T, Tanno S et al. Segmental groove pancreatitis accompanied by protein plugs in Santorini‘s duct. J Gastroenterol 1998; 33 (2): 289–294.

10. Gabata T, Kadoya M, Terayama N et al. Groove pancreatic carcinomas: radiological and pathological findings. Eur Radiol 2003; 13 (7): 1679–1684.

11. Isayama H, Kawabe T, Komatsu Y et al. Successful treatment for groove pancreatitis by endoscopic drainage via the minor papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61 (1): 175–178.

12. Arvanitakis M, Rigaux J, Toussaint E et al. Endotherapy for paraduodenal pancreatitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy 2014 (7); 46: 580–587. doi: 10.1055/s‑0034‑1365719.