Adjustable gastric balloons for weight loss – a higher yield of responders compared to non-adjustable gastric balloons

Adam Vašura1, Evžen Machytka1, Valenti Puig-Divi2, Fernando Saenger2, Ricardo Sorio2, Marek Bužga3, Jeffrey Brooks4

+ Affiliation

Summary

Introduction:

The degree of efficacy and duration of effect of the intragastric balloon (IGB) can be variable and unpredictable. The Spatz Adjustable Intragastric balloon (AIGB) was developed to extend implantation to 1 year, decrease the balloon volume for intolerance and increase the volume for a diminishing effect. The utility/efficacy and responder rate with the Spatz3 AIGB were the subjects of this study.

Methods:

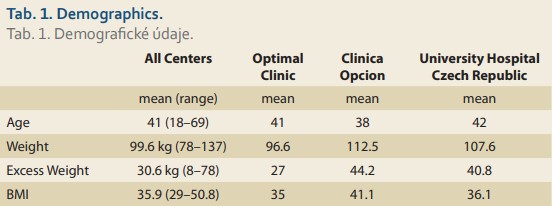

The results of 227 consecutive patients, without exclusions, in 3 centres implanted with the Spatz3 AIGB were reviewed retrospectively. Mean BMI 35.9; mean weight 99.6 kg; mean Excess Body Weight Loss (EBWL) 30.6%; mean balloon volume 464ml (400–500 ml). Balloon volume adjustments were offered: downward adjustments for intolerance and upward adjustments for weight loss plateau.

Results:

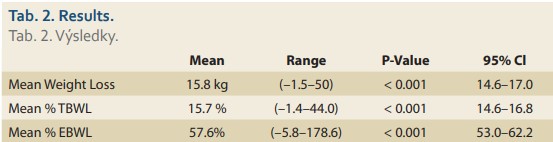

227 patients were implanted (mean 10.3 months) yielding a mean weight loss of 15.8 kg; mean 15.7% Total Body Weight Loss (TBWL) and 57.6% Excess Body Weight Loss (EBWL). Response (> 25% EBWL) was achieved in 83.3% of the patients. Downward adjustments in 15 patients (mean 2.3 weeks; mean –120 ml) allowed 12/15 (80%) to continue IGB therapy for a mean of 8.8 months. Upward adjustments in 107 patients (mean of 4.7 months; mean +284ml) yielded an additional mean weight loss of 8.5 kg. The upward-adjusted group at extraction had a mean weight loss of 17.8 kg; 17.2% TBWL and 59.2% EBWL. Two gastric ulcers: one due to NSAIDs and one healed with downward adjustment.

Conclusions:

In this retrospective review of 227 consecutive Spatz3 AIGB patients, upward adjustments yielded a mean 8.5 kg extra weight loss for those with a weight loss plateau, and downward adjustments alleviated early intolerance in 80% of the patients. These two adjustment functions may be instrumental in yielding a response rate of 83.3%

Keywords

obesity, weight loss, intragastric ballon, adjustable intragastric ballon, weight loss plateau, intolerance, excess body weight loss, total body weight lossIntroduction

Bariatric surgery has excellent results in therapy for obesity and components of metabolic syndrome, but there is a high rate of morbidity and a not negligible rate of mortality. Because of this, many gastroenterologists make efforts to investigate the best endoscopic method to reach weight loss. This bariatric endoscopy could be effective and with a lower rate of morbidity and mortality. For example, the EndoBarrier endoscopic duodenal-jejunal bypass is a safe and effective method [1]. Another method, for example, is an implantation balloon, filled with air or saline solution, in the stomach. These intragastric balloons (IGBs) have been used successfully for weight loss for the last 30 years [2,3]. The published results reveal an average weight loss of 12–15 kg, and 20–35% EBWL over 6 months with an excellent safety profile [4–15] The Spatz Adjustable balloon was introduced in 2010 as the first IGB approved for one year while featuring an adjustability function that afforded changes to the balloon volume as needed. The adjustability function was developed to address the issues related to IGBs; 1. variability of response and reduced efficacy after 1–3 months [16–18], and 2. intolerance necessitating early balloon extraction [5,19] – this was recently confirmed in the FDA trials for Reshape Duo and Orbera IGBs where there were reported 14% and 22% early extraction rates, respectively [20,21]. In addition, the FDA SSED reported that 53.6% of Orbera and 52% of Reshape subjects did not lose at least 10% of their total body weight (10% TBWL) or 25% of their Excess Weight (25% EBWL). A prospective study recently reported that 54.4% of the Orbera patients did not achieve 10% TBWL [18]. This group of unsuccessful patients (52–54.4%) is a significant number and should be addressed. With the advent of the Spatz adjustable balloon, it is conceivable that alleviating intolerance with a downward adjustment and renewing weight loss after upward balloon adjustment may be able to diminish the number of non-responders.

The results of the Spatz adjustable balloon system have been reported in four studies with weight losses of 24.4 kg (48.8% EBWL), 21.6 kg (45.7% EBWL),17.2 kg (42.9% EBWL) and 16.3 kg (67.4% EBWL), respectively [22–25]. The responder rate (>25% EBWL) was 88.5% in one recent study [24].

We report and analyse the results of 227 Spatz3 patients retrospectively reviewed in three centres– some adjusted and some not adjusted during the course of their 1-year implantation – to determine if the adjustment option can improve the overall results and diminish the non-responder rate.

Patients and methods

The Spatz3 Adjustable IGB (Spatz FGIA, Inc. NY, USA) was implanted at the following centres between May and December 2015: University Hospital, Ostrava, Czech Republic; Clinica Opcion Medica, Barcelona, Spain; and Optimal Clinic, Tel Aviv, Israel. The study had a retrospective, Case-Only, and open-label design (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: ID NCT03473938). The patients were selected according to the well-established criteria for intragastric balloon implantation, consistent with NIH [26] and CE Mark guidelines, and were independently evaluated by members of the staff: gastroenterologists, dietitians and psychologists. Indications for Spatz3 Adjustable IGB implantation included one of the following: 1. temporary weight loss treatment in a patient with a body mass index (BMI) in the range of bariatric surgery (>35) who refuses surgery or is at a high risk for surgery, 2. temporary weight loss treatment for a patient without indications for surgery (BMI > 29). All the patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy using conscious sedation with or without an anaesthetist using one or more of the following medications – Propofol, Midazolam and Fentanyl.

The balloons were inflated with a mean 464 ml (400–500 ml) of normal saline with the addition of 2–3 ml of a 1% solution of Methylene Blue (not used in the Czech centre). The patients recovered for 45 minutes and were discharged the same day on a once-daily PPI, anti-nausea medications (Aprepitant 125 mg day 1; 80 mg days 2 and 3), ondansetron (8 mg Q6H X 3 days), anti-spasmodic (papaverine 80 mg tid prn) and dietary instructions. After the fifth post-procedure day, a progressive full liquid to soft to solid 1,200–1,400 kcal diet was started. A monthly follow-up with a dietitian and/or doctor (gastroenterologist or endocrinologist) was offered to all patients after implantation. Cognitive behavioural therapy by licenced psychologists was offered in 2 of the 3 centres (206/227 patients) with 6–10 sessions after implantation. Patients who were intolerant of the balloon could have the volume adjusted downward by 100–150 ml. Patients with one or more of the following were offered upward adjustments of the balloon volume (200–400 ml at the discretion of the endoscopist): weight loss plateau; lack of effect of the balloon; ability to overeat without resultant symptoms (any of the following: nausea, vomiting, bloating, eructation, abdominal pain, acid reflux symptoms). Preparation for an adjustment or extraction procedure required the following diet: 3 days prior – no meat or vegetables; 2 days prior – full liquids; 1 day prior – clear liquids and NPO after midnight. After 12 months of placement, the balloon was deflated by aspiration via a standard balloon needle or deflation utilising the valve, and extraction was completed using a grasping forceps or a polypectomy snare – all under conscious sedation.

Statistics

The % TBWL, % EBWL and change in body weight from pre-implant were analysed using two-sided, one-sample t-tests, such that a statistically significant result indicates a mean different from zero. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals are also provided. For those with balloon extraction more than 12 months earlier, their last observation was carried forward (LOCF).

Results

From May 2015 to December 2015, 227 consecutive patients (176 female, 51 male) underwent Spatz3 AIGB placement in three centres. Four patients had their balloons removed within 14 hours after implantation due to severe intolerance and refusal to adjust the balloon downward. They included a mother and daughter who were implanted the same day and returned within 14 hours requesting removal due to severe nausea and weakness; a 47-year-old man who refused to take anti-nausea meds and at the first wave of nausea insisted on the balloon’s removal at 12 hours post implantation; and a 41-year-old woman with nausea and 2 episodes of vomiting that caused a panic attack 8 hours after the balloon placement. These 4 patients are included in our statistics. The 227 patients’ results are presented in this paper with their demographics for all patients and for each centre displayed in Tab. 1. The weight loss results are displayed in Tab. 2 with a mean loss of 15.8 kg, 15.7% TBWL and 57.6% EBWL. The response rates of the patients were 189/227 (83.3%) achieving > 25% EBWL; 157/227 (69.2%) achieving > 40% EBWL; 124/227 (54.6%) achieving > 50% EBWL.

Adjustments

Downward adjustments

Fifteen patients were intolerant of the balloon characterised by recurrent nausea, daily or sporadic vomiting in all, and recurrent abdominal pain in 6 of the 15 patients. The mean BMI in this group of intolerant patients was 34.5; mean weight 102.5 kg; mean excess weight 24.4 kg; mean balloon volume 463 ml. All fifteen underwent downward adjust ments of the balloon volume between 2 and 4 weeks (mean 2.3 weeks), and all experienced immediate relief of symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pressure). The first 6 had 100 ml removed; 3 of the 6 continued with the balloon therapy for at least 6 more months, however, the other 3 had a recurrence of symptoms within 1 week and required extraction within 3 weeks after downward adjustment. The next 9 had 150 ml removed (or 100 ml removed if the initial balloon volume was 400 ml) and all 9 continued with the balloon therapy for at least 8 more months. The weight loss results of the 15 patients (including the 3 who did not continue with the balloon treatment) after downward adjustment (using LOCF) was 16.1 kg (6.6–32.4 kg) of mean weight loss, mean TBWL 17.1% (7.5–26.9%), mean EBWL 73% (28.2–132.2%), mean implant time 8.8 month (1–14 months). There were 7 intolerant patients who refused downward adjustment and had their balloons extracted within the first 3 months.

Upward Adjustments

107 patients underwent upward adjustments at a mean 4.7 months (range 2–7 months) with a mean addition of 284 ml (range 200–400). In this group of 107 patients the mean weight was 102.5 kg; mean BMI 36.4; and the mean excess weight was 33.3 kg. There were several reasons for patient request for upward adjustment, and the patients had more than 1 reason in many cases. All had a weight loss plateau; 40 requested renewal of the initial strong balloon effect in order to achieve a second round of rapid weight loss; and 74 reported a decrease in overeating-induced symptoms (nausea, pain, vomiting, eructation, heartburn etc.) and wanted this balloon effect renewed.

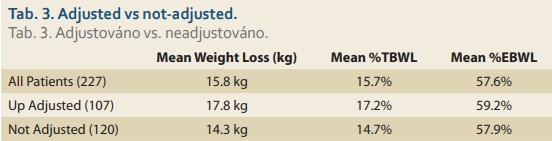

The additional mean weight loss following upward adjustment was 8.5 kg, which is an additional 8.3% TBWL and 25.8% EBWL. The final results of the 107 upward adjusted patients were 17.8 kg weight loss; 17.2% TBWL and 59.2% EBWL. Although this is not a randomised control study and conclusions cannot be drawn, nevertheless, the differences in the final results between the upward-adjusted patients and non-adjusted patients are seen in Tab. 3 and it seems that the group with upward adjustment had better results (mean 17.2% TBWL upward adjusted vs. mean 14.7% TBWL non-adjusted).

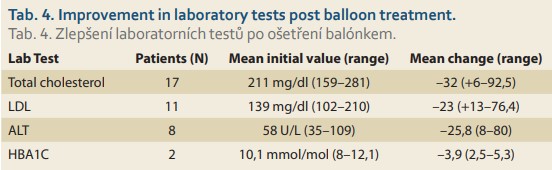

Laboratory and Medical improvements

Two patients with hypertension were able to stop or decrease their medications after weight loss of > 10% TBL. The improvement in the laboratory tests post balloon treatment was available for review as displayed in Tab. 4.

Follow-up visits

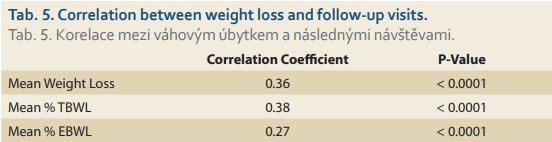

The number of follow-up visits correlated with the degree of success in weight loss. As displayed in Tab. 5, there is a tendency toward better weight loss as the number of follow-up visits with the dietitian/doctor increases.

Complications

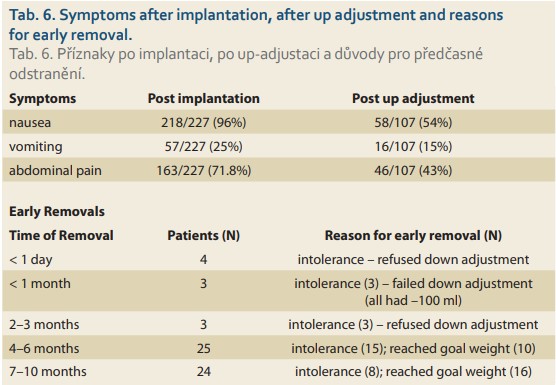

Symptoms of nausea, vomiting or abdominal pain were reported after implantation and after upward adjustment. The symptoms were less frequent after the upward adjustment as seen in Tab. 6, together with the details of the causes of early removal. 59/227 balloons were extracted prior to the end of 10 months – 33 for continued intolerance and 26 for reaching the goal weight; 3 underwent downward adjustment, however they eventually underwent extraction due to continued symptoms in the first month; 3 refused downward adjustment between months 2–3; 23 had the balloons removed between months 4 and 10 due to mild continuous intolerance; and 26 reached their goal weight (> 40% EBWL) between months 4–10.

Two gastric ulcers were noted: One at 5 months and one at 12 months. At 5 months a bland 1 cm × 5 mm ulcer was found in a symptomatic patient. The balloon was adjusted downward (–150 ml), which alleviated the symptoms and which had healed completely by a follow-up endoscopy at 8 months. The second ulcer was a 1 cm × 1 cm bland ulcer found during the 12-month extraction endoscopy in a patient who took 1200 mg Advil daily for 1 week to alleviate a headache. The ulcer had healed (proton pump inhibitors twice daily) upon follow-up endoscopy 2 months later.

Aspiration pneumonia was reported in one patient after the extraction procedure and was treated successfully as an outpatient with Augmentin (875 mg per oral twice daily for 10 days).

There were no balloon deflations, bowel obstructions or viscous perforations.

Discussion

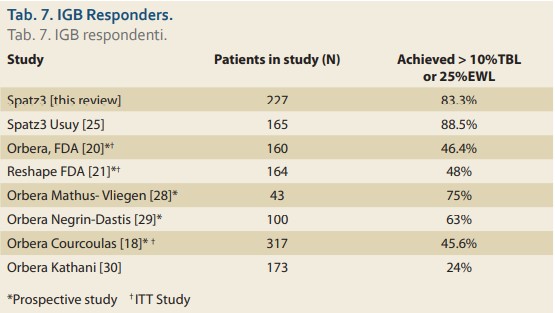

In our experience, IGBs assist obese subjects by providing two phases of weight loss. The first phase is the initial ‘storm’ in which oral intake is severely restricted, resulting in rapid weight loss. The length of this phase is variable, lasting anywhere from days to several weeks. This is followed by the prolonged phase of balloon ‘monitoring’ in which balloon restriction of oral intake is minor but overeating-induced symptoms (nausea, vomiting, pain, eructation, heartburn, bloating) are the major effect. These symptoms are the negative re-enforcement that contributes to behaviour modification. The patients need to understand that the resolution of the phase 1 ‘storm’ does not herald the end of the IGB effect. As long as the balloon causes enough GI symptoms after over-eating, there is no need to enlarge the balloon, in our experience. Once the symptoms induced by over-eating diminish, that is the time to consider balloon enlargement. The length and strength of phase 2 are also highly variable, lasting from weeks to many months. A recently published randomised controlled study demonstrated that IGBs function, at least in part, by delaying gastric emptying. Nuclear gastric emptying studies were performed pre-implantation, post implantation and post extraction on Orbera balloon subjects and on control subjects for comparison. During pre-implantation, approximately 22% of the food was retained in the stomach 2 hours after ingestion in the balloon and control subjects. Post balloon implantation nuclear studies revealed approximately 62% of the food was retained in the stomach 2 hours after ingestion, and this returned to baseline approximately 1 month after balloon extraction [27]. This can explain why IGB patients who overeat develop a progressive gastric accumulation of food. The retained food plus the balloon cause excessive stomach wall pressure which can produce symptoms (nausea, vomiting, pain, eructation, heartburn, bloating). The study reported a direct correlation between the degree of gastric retention and the degree of weight loss – patients with greater post prandial gastric retention lost more weight than those with les ser gastric retention [27]. This variability of phase 2 can be seen in the ‘response rate’ and cannot be discerned from the mean results alone, since huge weight losses in a relatively small number of responders can offset small weight losses in many non-responders. There are a plethora of IGB papers that report the overall success of IGBs based on mean weight loss, mean % TBWL and mean % EBWL. Yet, in our review, the percentage of responders/non-responders is not often reported. The FDA has established in several pivotal IGB trials that response is defined as > 10% TBWL or > 25% EBWL [20,21]. We found 7 reports that disclosed the percentages of responders as displayed in Tab. 7. The two Spatz studies report a higher responder rate than those reported with 6-month non-adjustable balloons.

We can only conjecture that the Spatz3 balloon has a lower non-responder rate due to alleviation of intolerance with downward adjustments and additional weight loss with upward adjustment. In other words, saving subjects from early extraction and adding extra weight loss when the balloon effect diminishes, may be responsible for the overall higher response rate. The downward adjustment for early intolerance in our study enabled 80% of those patients to continue balloon therapy without compromising the weight loss effect. This is consistent with four previously published Spatz3 studies which reported successful alleviation of early intolerance in 3/3, 26/26, 10/13 and 16/20 intolerant patients, respectively [24,25,31,32]. Upward adjustments in our study effectively promoted renewed mean weight loss of 8.5 kg, which is consistent with previously published Spatz3 data, which reported additional weight loss after upward adjustments of 8.2 kg, 8.9 kg, 5 kg and 5.7 kg [24,25,31,32].

Based on our retrospective review of 227 consecutive patients (none excluded in our calculations) in three centres, the Spatz3 AIGB is an effective device for weight loss with limited morbidity beyond the expected early intolerance. It appears to have a higher rate of patient responders compared to non-adjustable 6-month balloons, however this needs to be further clarified with prospective studies. Nonetheless, we suggest that the response rate is an additional piece of information that should be included in studies and reviews, since patients and doctors need to be aware not only of the mean results, but also of the chance of a successful outcome.

Ethical approval

All the procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, University of Ostrava, Czech Republic, in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Adam Vašura, MD

Department of Gastroenterology

Internal Clinic

University Hospital Ostrava

17. listopadu 1790/5

708 52 Ostrava-Poruba

Czech Republic

adam.vasura@fno.cz

Submitted/Doručeno: 18. 8. 2020

Accepted/Přijato: 30. 11. 2020

To read this article in full, please register for free on this website.

Benefits for subscribers

Benefits for logged users

Literature

1. Beneš M, Hucl T, Drastich P et al. Endoskopický duodenojejunální bypass (EndoBarrier®) jako nový terapeutický přístup u obézních diabetiků 2. typu – efektivita a faktory predikující optimální efekt, Gastroent Hepatol 2016; 70 (6): 491–499.

2.. Abu Dayyeh B, Edmundowicz SA, Jonnalagadda S et al. Endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81 (5): 1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.02.023.

3. Choi SJ, Choi HS. Various intragastric balloons under clinical investigation. Clin Endosc 2018; 51 (5): 407–415. doi: 10.5946/ce.2018.140.

4. Ashrafian H, Monnich M, Braby TS et al. Intragastric balloon outcomes in super-obesity: a 16-year city center hospital series. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14 (11): 1691–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.01.010.

5. Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Álvarez EE et al. Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2008; 18 (7): 841–846. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9331-8.

6. Kumar N, Bazerbachi F, Rustagi T et al. The influence of the orbera intragastric balloon filling volumes on weight loss, tolerability and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2017; 27 (9): 2272–2278. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2636-3.

7. Genco A, Maselli R, Cipriano M et al. Long-term multiple intragastric balloon treatment--a new strategy to treat morbid obese patients refusing surgery: prospective 6-year follow-up study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014; 10 (2): 307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.013.

8. Roman S, Napoléon B, Mion F et al. Intragastric balloon for „non-morbid“ obesity: a retrospective evaluation of tolerance and efficacy. Obes Surg 2004; 14 (4): 539–544. doi: 10.1381/096089204323013587.

9. Buzga M, Kupka T, Siroky M et al. Short-term outcomes of the new intragastric balloon End-Ball® for treatment of obesity. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2016; 11 (4): 229–235. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2016.63988.

10. Bazerbachi F, Haffar S, Sawas T et al. Fluid-filled versus gas-filled intragastric balloons as obesity interventions: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes Surg 2018; 28 (9): 2617–2625. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3227-7.

11. Vargas EJ, Rizk M, Bazerbachi F et al. Medical devices for obesity treatment: endoscopic bariatric therapies. Med Clin North Am 2018; 102 (1): 149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08. 013.

12. Lopez-Nava G, Bautista-Castaño I, Jimenez-Baños A et al. Dual intragastric balloon: single ambulatory center spanish experience with 60 patients in endoscopic weight loss management. Obes Surg 2015; 25 (12): 2263–2267. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1415-6.

13. Neto MG, Silva LB, Grecco E et al. Brazilian Intragastric Balloon Consensus Statement (BIBC): practical guidelines based on experience of over 40,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14 (2): 151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.09.528.

14. Busetto L, Segato G, De Luca M et al. Preoperative weight loss by intragastric balloon in super-obese patients treated with laparoscopic gastric banding: a case-control study. Obes Surg 2004; 14 (5): 671–676. doi: 10.1381/09608 9204323093471.

15. Doldi SB, Micheletto G, Perrini MN et al. Treatment of morbid obesity with intragastric balloon in association with diet. Obes Surg 2002; 12 (4): 583–587. doi: 10.1381/096 089202762252398.

16. Bonazzi P, Peterlli MD, Lorenzini I et al. Gastric emptying and intragastric balloon in obese patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2005; 9 (5 Suppl 1): 15–21.

17. Totté E, Hendrickx L, Pauwels M et al. Weight reduction by means of an intragastric device; experience with BIB. Obes Surg 2001; 11 (4): 519–523. doi: 10.1381/096089201321209459.

18. Courcoulas A, Abu Dayyeh BK, Eaton L et al. Intragastric balloon as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Int (Lond) Obes 2017; 41 (3): 427–433. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.229.

19. Mathus-Vliegen EMH. Intragastric balloon treatment for obesity: what does it really offer? Dig Dis 2008; 26 (1): 40–44. doi: 10.1159/000109385.

20. FDA SSED Orbera Balloon. PMA P140008: FDA Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data. 2015 [online]. Available from: https: //www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf14/P140008b.pdf.

21. FDA SSED Reshape Duo Balloon. PMA P140012: FDA Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data. 2015 [online]. Available from: https: //www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/ pdf14/P140008b.pdf.

22. Machytka E, Klvana P, Kornbluth A et al. Adjustable intragastric balloons: a 12-month pilot trial in endoscopic weight loss management. Obes Surg 2011; 21 (10): 1499–1507. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0424-z.

23. Brooks J, Srivastava ED, Mathus-Vliegen EMH. One-year adjustable intragastric balloons: results in 73 consecutive patients in the UK. Obes Surg 2014; 24 (5): 813–819. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1176-3.

24. Machytka E, Brooks J, Buzga M et al. One year adjustable intragastric balloon: safety and efficacy of the Spatz3 adjustable balloons. 2014 [online]. Available from: http: //f1000research.com/articles/3-203/v1#DS0.

25. Usuy E, Brooks J. Response rates with the Spatz3 adjustable balloon. Obes Surg 2018; 28 (5): 1271–1276. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2994-x.

26. NIH conference. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus development conference panel. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115 (12): 956–961.

27. Gómez V, Woodman G, Abu Dayyeh BK. Delayed gastric emptying as a proposed mechanism of action during intragastric balloon therapy: results of a prospective study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016; 24 (9): 1849–1853. doi: 10.1002/oby.21555.

28. Mathus-Vliegen EMH, Tytgat GNJ. Intragastric balloon treatment for obesity: safety, tolerance and efficacy of 1-year balloon treatment followed by a 1-year balloon-free follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61 (1): 19–27. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107 (04) 02406-x.

29. Negrin Dastis S, François E et al. Intragastric balloon for wt loss: results in 100 individuals followed for at least 2.5 years. Endoscopy 2009; 41 (7): 575–580. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214 826.

30. Kahtani KA, Khan MQ, Helmy A et al. Bio-enteric intragastric balloon in obese patients: a retrospective analysis of King Faisal Specialist Hospital experience. Obes Surg 2010; 20 (9): 1219–26. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9654-8.

31. Machytka E, Marinos G, Kerdahi R et al. Spatz Adjustable Balloons: Results of Adjustment for Intolerance and for Weight Loss Plateau. Gastroenterology 2015; 148 (4): S900.

32. Brooks J, Tsvang E, Ganon M et al. Spatz3 Adjustable Balloon: Early Adjustment to Prevent Premature Extraction. Gastroenterology 2016; 150 (4): S826.